Children’s Drawings from the Terezín Ghetto, 1942-1944

The exhibition is on the first floor of the Pinkas Synagogue

The story of children deported to the Terezín ghetto

Comprised of 19 sections, this exhibition outlines the story of Jewish children deported to the Terezín ghetto during the Second World War. In 1941–1945, Terezín served as a way station to the concentration and death camps in the east.

The story begins with reflections on the events immediately following 15 March 1939, when Bohemia and Moravia were occupied by the Nazis and transformed into a Protectorate. This is followed by a description of transports to the Terezín ghetto (starting on 24 November 1941), everyday ghetto life and the conditions in the children's homes.

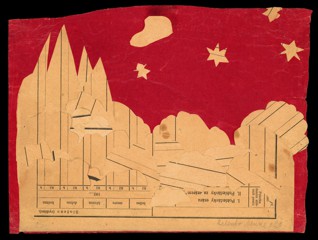

There are also depictions of holiday celebrations and of the dreams that the imprisoned children had of returning home or of travelling to Palestine. This section provides a sort of poetic interlude between the brutal uprooting from their homes and deportation to Auschwitz, which is the final and most tragic chapter of the whole story.

Friedl Dicker-Brandeis and art classes in Terezín

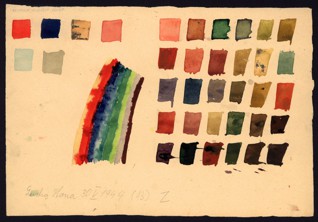

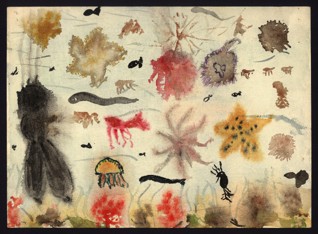

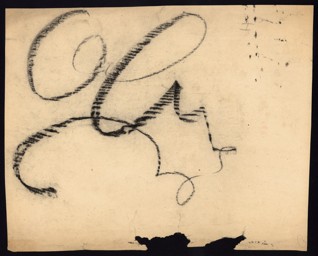

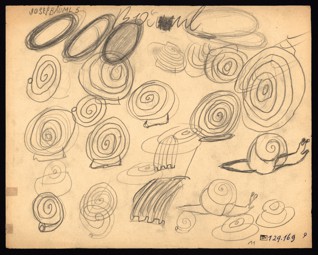

The story is depicted through children’s drawings which were created in the Terezín ghetto between 1942 and 1944.

These drawings were made during art classes that were organized by Friedl Dicker-Brandeis (1898–1944), a painter, interior and stage designer, graduate of the Bauhaus, and pupil of Franz Čížek, Johann Itten, Lyonel Feininger, Oskar Schlemmer and Paul Klee.

As part of what was mostly a clandestine education programme for children at Terezín, the art classes were very specific in nature, reflecting the progressive pedagogical ideas that Friedl Dicker-Brandeis had adopted during her studies at the Bauhaus (especially in the initial course developed by Johannes Itten). Drawing was seen as a key to understanding and a way of developing basic principles of communication, as well as a means of self-expression and a way of channelling the imagination and emotions. From this perspective, art classes also functioned as a kind of therapy, in some way helping the children to endure the harsh reality of ghetto life.

Drawings as the only reminders

Before being deported to Auschwitz, Friedl Dicker-Brandeis filled two suitcases with about 4,500 children's drawings and put them in a secret place; immediately after the war, they were recovered and handed over to the Jewish Museum in Prague. These drawings are a poignant reminder of the tragic fate of Bohemian and Moravian Jews during the Second World War. Only a few of the Terezín children survived. The vast majority were deported to Auschwitz where they faced certain death.

These pictures are often all that is left to commemorate the children's lives. Without them their names would be remain forgotten.

![[subpage-banner/2_pamatkyaexpozice_2.png]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/subpage-banner/2_pamatkyaexpozice_2.png)

![[design/2013/Twitter.png]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/design/2013/Twitter.png)

![[design/2013/Instagram.png]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/design/2013/Instagram.png)

![[homepage-banner/incident.jpeg]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/homepage-banner/incident.jpeg)