Restitued Works of Art - The Collection of Dr. Emil Freund

From 06. 09. 2001 to 06. 01. 2002

10am - 5pm, except Saturdays and Jewish holidays

Robert Guttmann Gallery, U Staré školy 3, Praha 1

On first glance the paintings and drawings the Jewish Museum in Prague has selected to present in its exhibition "Restituted Works of Art" seem not to have much in common. They are not connected by a single distinctive style and one would be hard put to find among them a common theme. Yet an innate relationship between the works exhibited here does undeniably exist. The nature of this relationship was determined by the events of one night - 14-15 March, 1939 -when the German Army occupied the rump of Bohemia and Moravia, thereby altering forever the fates of their original owners.

The paintings and drawings that came from these private collections serve as silent witnesses to the human tragedy. These are works of art that, having been touched by their owners, are endowed with memory, works of art whose story to some extent mirrors the story of those with whom they spent a part of their lives. Between these objects and their owners, however, there is one important difference: the art survived, their owners did not.

The art plundered during the war was documented immediately after liberation by teams of experts drawn from the ranks of the allied forces. They undertook an extensive search for artworks that had been displaced, especially to the occupied zones of Germany and Austria. Though lengthy lists of missing art objects were published, only a fraction of the art stolen during the war and transported to unspecified locations was ever successfully tracked down. The documentation that would have allowed for a more detailed examination of what actually happened to the stolen art was largely destroyed at the war's end, and those documents that were not destroyed remained buried for years in archives.

Only when these wartime documents were declassified fifty years later did a space open in which the search for stolen art could take place. Studies of the newly accessible archival material have been providing experts with the information they need to fill the gaps in the provenance of many important works of art that for years have been permanent fixtures in recognized public galleries.

Even though it is common for curators of museums and galleries to conduct a full provenance research of the art found in their collections, special emphasis should be placed on investigating ownership during the period 1933-1945. This was the conclusion of participants at the first conference devoted to the question of confiscated property of Holocaust victims which was held in Washington D.C. in November 1998. In an effort to complete this task , the leading world museums and galleries conducted thorough provenance research on their collections. The findings of this research are available to the general public in the form of a database that can be accessed through the internet.

The Jewish Museum in Prague has also joined these efforts by conducting its own provenance research. Over the past few years the museum has made a comprehensive study of collections of paintings, drawings, and graphic art which were assumed to contain works whose original owners could be verified. Among these was also the art restituted to the Jewish Museum from the National Gallery in Prague, where it had been stored since 1950 by order of the former communist regime. With few exceptions, these works of art were never exhibited, and their actual provenance was of little interest to the National Gallery. Today, a list of these artworks, including photo-documentation, is publicly available on the websites of the Jewish Museum (http://www.jewishmuseum.cz) and the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic (http://www.restitution-art.cz). In the event that a valid restitution claim is put forward in accordance with the relevant law regarding these or any other works in the Jewish Museum's collection, the museum is prepared to return the art to the heirs of the original owner.

The fate of art looted during the Holocaust in many respects resembles the fates of the millions who had their lives shattered over a twelve-year period during the 20th century. Historians are still hard at work to reconstruct these lives one after another to rescue them from the oblivion of being an eternal statistic. In the same period tens of thousands of artworks connected to these lives were expropriated and transferred to unspecified locations. Researching these fates should be understood as an integral part of the effort to construct as precisely as possible the unique, concrete human identity to whom they belonged, the identity of someone with their own traditions, who loved their native land, family, and culture, irrespective of what language predominated in that culture.

Thanks to the selfless work of Jewish scholars during the war, a number of exceptional examples of Jewish culture in Bohemia and Moravia, which had thrived for over a thousand years, were gathered - and thus rescued - into the collection of the Jewish Museum. For this reason the present-day Jewish Museum considers provenance research of these preserved objects an essential aspect of its mission.

Originally founded as an association and focussing on collecting and preserving the legacy of the disappearing world of the Jewish Ghetto - similar to other such institutions founded in Central Europe at the beginning on the 20th century - the museum has since taken on, in the context of European Jewry's tragic experience during the war, a new, vitally important task : to look after and preserve the heritage of those deported and murdered. This is also why the Jewish Museum in Prague attaches such importance to documenting all spheres of Jewish culture, including those spheres that mixed with, and in some cases completely identified with, other ethnic cultures. In this sense the Jewish Museum is no longer merely an institution housing decontextualized objects divested of their original functions; rather, it is becoming an institution where priority is given to the preservation and understanding of the Jewish cultural heritage as an historical and social phenomenon. In addition to collecting Judaica, Jewish collectors in Bohemia and Moravia played a significant role in systematically documenting the development of Czech and German art, if not European art in general. And this is why it is so important to document their activities.

Dr. Emil Freund's Collection

The art formerly belonging to Emil Freund represents one of the rare cases where at least part of an art collection was successfully kept together as it passed through the Treuhandstelle, the warehouse in Prague, where during the war movables from the apartments of persons deported from the city and its immediate surroundings were amassed.

The biographical data on this largely forgotten art collector is rather scanty. We only know that he was born April 29, 1886 in Svatý k íž near Havlíčkův Brod to Karel and Regina Freund as the second of four children. During his career as an insurance lawyer he achieved the post of director of the Prague insurance company Sekuritas. Apparently he owned a modest collection of modern art - paintings, drawings, and graphic prints - which was housed in his apartment at 9 Mánesova Street in Prague's Vinohrady district. This is his last known address. Presumably it was here that these artworks, along with other items from the apartment's furnishings, were secured and then, as confiscated Jewish property, transferred in October 1941 to the Treuhandstelle. On October 21, 1941 Freund was deported from Prague on transport B to the Łódź Ghetto where he died on September 13, 1942. The memory of Freund survived only thanks to the fact that between 1943 and 1944 a major part of his collection was incorporated into the collection of the Central Jewish Museum in Prague.

Judging from the fragments that were preserved, and that for us today represent the sole source of information on Freund's activities as an art collector, the collection was begun during the interwar period. The larger part was formed by acquisitions from exhibition sales, such as those organized in Prague by the Spolek výtvarných umelců Mánes (Association of Fine Artists Mánes) and a number of other private galleries. Even though the collection was in no way comparable in its breadth and significance to the leading modern art collections of the day, it was comparable in its selection of artists. Most prominent were the works of Czech and French artists from the interwar period. In the part of the collection that we have available today, the only painting that somewhat deviates from this time frame is Paul Signac's Riverboat on the Seine (Morning in Samois) from 1901, probably purchased at one of the exhibitions of French art held by SVU Mánes. In addition to the Signac, Freund gradually added to the collection other first-rate works, such as Head of a Young Woman by André Derain and a landscape painting by Maurice Utrillo entitled Le donjon rue des Veaux, - Vire,Calvados. A watercolor by Utrillo depicting a view of the Church of St. Peter in Montmartre is also in the collection, as is a group of four gouaches by Maurice Vlaminck . Regarding the latter, these lyrical pictures of the French countryside were in all probability an incidental purchase acquired as one set and included in the collection only provisionally. Freund likely counted on replacing them with a more notable work by Vlaminck .

Among Czech painters, Freund acquired works by Emil Filla, Jan Bauch, Zdenek Rykr, Alfred Justitz, Emil Arthur Pittermann-Longen and Václav Špála. Not even here was the collection all that balanced, and we can only assume that he intended to continue adding to it and thereby give it a more polished, coherent form.

In asking the question whether Freund was a true collector or just a lover of art who liked to surround himself with choice works of art, we should keep in mind that his collection developed with considerably less means-and therefore much more slowly-than other great collections. The fact that his individual acquisitions were divided by larger intervals of time (no doubt because of lack of suitable opportunities to buy as well as financial constraints) meant that Freund needed more time to develop a more extensive and, especially, a more balanced collection. Even though he was not given this time, the same as with many other Jewish collectors, the fragment of Freund's collection that has survived does allow one to glimpse his sophisticated taste, which in the main was close to the circle of collectors active in the Sdružení přátel moderní galerie (Friends of Modern Galleries Association).

From today's perspective, Freund's collection, which in itself is a valuable historical document, should be understood as a dialogue violently interrupted.

Exhibition curator:Michaela Hájková

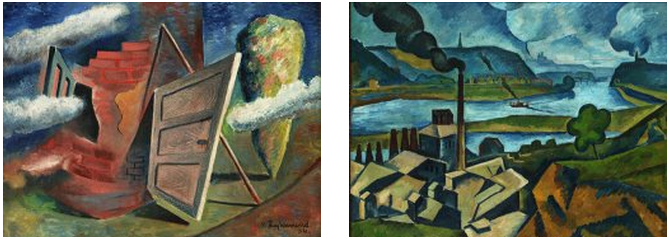

Left: Emil Filla: A Still Life with a Tray and a Bottle of Wine, 1931

Right: Maurice de Vlaminck: A Way through a French Village, around 1930

Left: Václav Zikmund: An Abandoned House, 1934

Right: Bohumil Kubišta: A View of the Bráník Cement Works, 1911

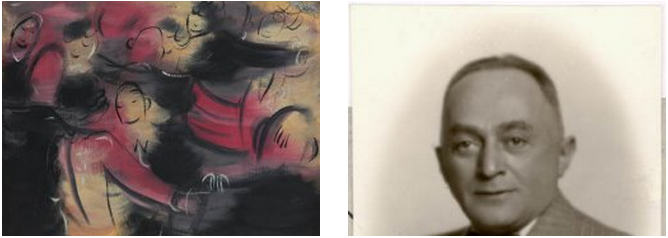

Left: Zdenek Rykl: Dance in a Café, 1930

Right: photograph of JUDr. Emil Freund, 1935, Studio Langans, Prague

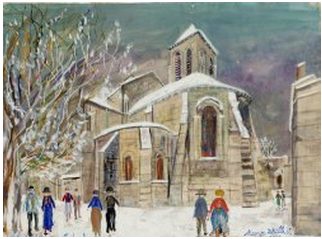

Maurice Utrillo: St Peter's Church at Monmartre, 1930

![[subpage-banner/3_Programavzdelavani_3.jpg]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/subpage-banner/3_Programavzdelavani_3.jpg)

![[design/2013/Twitter.png]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/design/2013/Twitter.png)

![[design/2013/Instagram.png]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/design/2013/Instagram.png)

![[homepage-banner/incident.jpeg]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/homepage-banner/incident.jpeg)