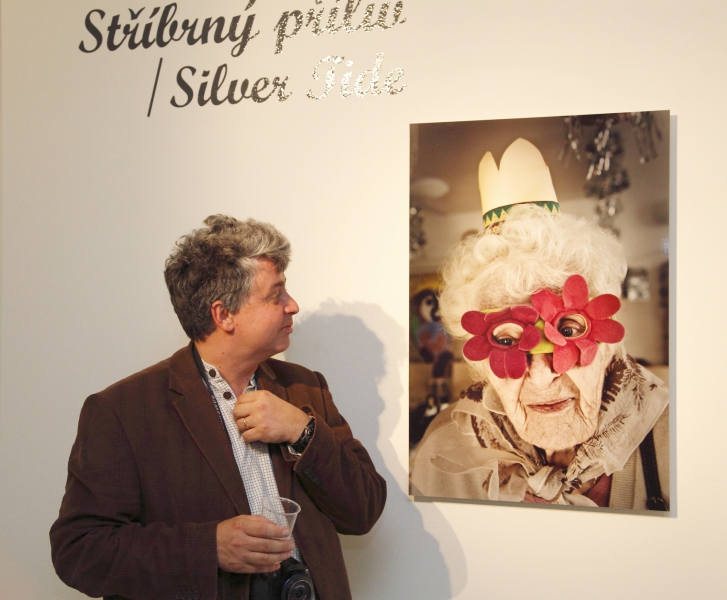

"Karel Cudlín – Silver Tide Part of the Jewish Presence in Contemporary Visual Art series"

From 15. 09. 2012 to 05. 02. 2012

"open every day except for Saturdays and Jewish holidays9 am – 4.30 pm"

Robert Guttmann Gallery, U Staré školy 3, Praha 1

This exhibition, curated by Michaela Sidenberg, provides a glimpse into the life of senior citizens at the Jewish community's Hagibor social care facility through photographs by the leading Czech documentary photographer Karel Cudlín (b. 1960).

Part of an extensive project that Cudlín has been involved in for several years, these works transcend the narrowly defined genre of social documentary photography. In his work Cudlín draws on the tradition of humanistic photography which, more often than not, involves establishing close relationships with his 'models'. It is precisely in this vein that Cudlín has conceived his comprehensive photo series and powerful portraits that are the focus of this exhibition. Reminiscent of chiaroscuro paintings, Cudlín's photographs offer a unique visual testimony to human life, of which old age is an essential, if often overlooked, part. It may be said that one of the main aims of this show is to explore the nature of beauty and its perception, which is often burdened with stereotypes. It concerns an attempt to depict the elderly not as victim survivors that are seen merely as a source of memory and as recipients of social care, but also as individuals to whom the adjectives 'beautiful', 'spirited' or 'humorous' may naturally be applied and whose strength is not necessarily proportional to their physical prowess. This exhibition will provide a not entirely usual perspective at a phenomenon that is becoming an increasingly frequent topic in contemporary visual art, as is evident from many other projects of a similar type (to date, mostly outside the Czech Republic).

Karel Cudlín (b. 1960) is often called a documentary photographer in the well-established tradition of humanistic photography of the 1940s and 50s, whose leading lights, chiefly Henri Cartier-Bresson, founded the Magnum agency. Cudlín’s work also shows a strong affinity with American street photography, and as with many of his predecessors and contemporaries, his photographs often go beyond classic photojournalism. Though his shots might always come from an unmanipulated reality, more often than not his infallible sense of composition, light, gesture, and expression guides him to isolate the situation as if it stood outside of time and space. A few years ago, the Czech novelist Jáchym Topol tried to fathom how this mechanism of a “reporter’s shot of eternity” worked, how it turned the banal moment into an icon. In his afterword to Journey to the East, a book of photography he co-authored with Cudlín, he admitted to having failed to uncover the secret of the cause, yet he was incisive in elucidating the effect: “The photo, torn from reality, delivers a message to eternity.” In relation to the faces of those who survived the Shoah, this is a message of unrepeatable urgency. The spontaneously composed images achieve their remarkable immortality thanks to the singular eye of the photographer. They remain in our memory as if they were still alive, and this is what’s most important.

The Hagibor nursing home in Prague is the most significant project undertaken by the Jewish Community of Prague since 1938. Its primary purpose is to provide a wide spectrum of social services to seniors who survived the Shoah. Special emphasis is placed on tailoring to individual needs and preserving human dignity when one is in the position of requiring end of life care. The home is also an open community center whose program is intended for all generations.

Care for the elderly and needy has a long tradition at Hagibor. Known as the “Israelite” hospice, it was built by the Jewish Community in 1911 and was in operation until 1943. At the beginning of WWII it served as a provisional school and shelter, its adjacent grounds providing an area for Jewish children to play and exercise. In the last years of the war it was turned into a detention camp for Jewish spouses of mixed marriages. Those imprisoned here were used to strip mica, a mineral important for the German arms industry. Around 3,500 people passed through the camp, and they were gradually transported to the Terezín Ghetto. After the war the property was returned to the Prague Jewish Community, but shortly thereafter it was again confiscated by the state and allocated to the nearby Vinohrady hospital for their use. Hagibor was finally restituted to the Jewish Community of Prague in 2006, and the foundation stone for the new building was laid the same year. Construction was completed in 2008, and in May of that year the first residents moved in.

Patronage exhibition

With the kind support of The Jewish Community of Prague Foundation

![[subpage-banner/3_Programavzdelavani_3.jpg]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/subpage-banner/3_Programavzdelavani_3.jpg)

![[design/2013/Twitter.png]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/design/2013/Twitter.png)

![[design/2013/Instagram.png]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/design/2013/Instagram.png)

![[homepage-banner/incident.jpeg]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/homepage-banner/incident.jpeg)