"And you shall tell your son… Haggadot in the collections of the Jewish Museum in Prague"

From 25. 03. 2010 to 27. 06. 2010

Guided tours of the exhibition:

open every day except for Saturdays and Jewish holidays

from 25 until 26 March 9 a.m. – 4.30 p.m.,

from 28 March until 27 June 9 a.m. – 6 p.m.

Robert Guttmann Gallery, U Staré školy 3,

"And you shall tell your son on that day, saying: “It is because of this that Hashem acted on my behalf when I left Egypt. (Exodus 13:8)

The Pesah story, as recounted in the Haggadah text recalls the events that occurred as Israel came into existence as an independent nation – the Exodus from Egyptian slavery by the Lord, the G-d of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob."

From generation to generation, its narrators and listeners are those who observe the commandment established in the Torah which provides the title of this exhibition of Pesah Haggadot from the collections of the Jewish Museum in Prague.

Pesah is primarily about the triumphant struggle for freedom alongside the Lord. Although the Paschal story speaks about the whole of Israel and its slavery in Egypt, we are clearly encouraged to grasp the deep personal and essentially topical dimension of the entire story, for it is written: “...It is because of this that Hashem acted on my behalf when I left Egypt” (Exodus 13:8). This personal imperative, albeit revealed to each generation in a direct way through participation in the Pesah drama, continually forms or re-establishes a bond with tradition and integrates the individual into Israel’s collective experience. The telling of the Pesah story is a means not only by which the timeless unity of the whole of Jewry is constituted, but also by which the essentially personal aspect of the story is stressed: a recognition of the personal experience of a people who lack freedom, whatever the cause of this may be. In this sense, the entire celebration of the Pesah holiday gives rise to a dualism of mythic freedom, which is the result of the Lord’s intervention in benefit of Israel, and individual servitude whereby each of us lives in our own galut, our own private Egypts, fettered with chains that we have made ourselves, but which are none the less onerous for that.

So let us grasp this unique opportunity and transform the Pesah holiday not only into a reminder of sufferings and wrongs, a celebration of Israel’s regained freedom and an expression of hope and expectation, but also into a call to move forward from our comfortable “freedom from” to a genuine, transcendental freedom, uniquely embodied in the supreme act of G-d’s mercy as recounted in the beautifully written, religiously significant and spiritually uplifting text of the Pesah Haggadah.

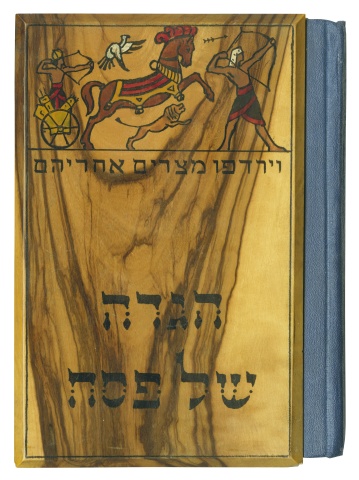

The Haggadah through the centuries

The Haggadah, together with the Mahzor and the Siddur, is among the most popular liturgical books of Judaism and is the most printed books of Jewish culture. Unlike the Mahzor and the Siddur, however, the visual appearance of the Haggadah has substantially changed in the course of more than ten centuries. While prayer books usually contain a simple text without illustrations, the Haggadah has, since the early manuscripts and printed versions, been adorned with illustrations that reflect the events of the narrated story in various forms and manifestations. The illustrations are intended to provide vivid lessons and to keep the attention of those partaking of the Pesah meal – especially children, who often found the celebration overly long. This is why modern editions of Haggadot often resemble children’s picture books, and even Haggadah comics have been produced.

What does the Haggadah tell us? It outlines the acts associated with preparations for the Pesah, sets out the order of the home service, describes the ritual ceremonies associated with the celebration, specifies the prayers to be said and the food and drink to be consumed during the seder, and, above all, recounts the biblical story of the Israelite Exodus from Egypt. The actual biblical text is supplemented by commentaries from the Midrashim, Talmudic texts, psalms and blessings; traditional seder songs are usually added to the end. Haggadah editions are often supplemented by extensive commentaries and scholarly interpretations by the rabbis responsible for the specific editions; translations into other languages were usually added in the later period.

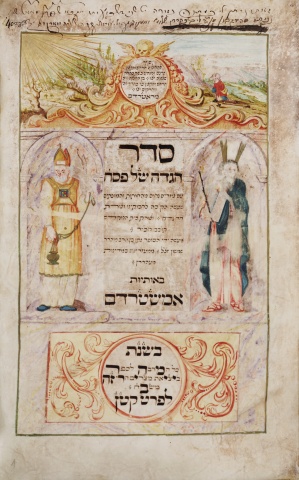

The final version of the basic text of the Haggadah was compiled in the seventh or eighth century C.E. by the Gaonim of Babylonia, although its oldest extent version dates from the tenth century and is part of the Siddur of Saadia ben Yosef Gaon. The second oldest completely preserved text is also not a separate work, but is part of the Mahzor Vitry, a twelfth-thirteenth century prayer book. Minor textual differences can still be found in Haggadah manuscripts until the fifteenth century. Any differences that appear in present-day Haggadot are reflective of specific rituals and local customs. The earliest separately preserved Haggadah manuscript dates from the thirteenth-fourteenth century. Three main types of Haggadah can be distinguished from the ornamentation and illustrations in these manuscripts. Sephardi Haggadot contain, in addition to the actual text, miniatures depicting biblical stories and piyyutim (religious poetry). Among the most important examples of this group are the Kaufmann Haggadah (Spain, fourteenth century), the Sarajevo Haggadah (Barcelona, fourteenth century) and the Golden Haggadah (Spain, probably Barcelona, 1320).

Haggadot from the Ashkenazi area, i.e. Germany and France, constitute a different type. These are usually adorned with miniature contextual illustrations in the margins of the text, which depict traditional customs and biblical stories. Only later examples contain scenes from the Bible that are not directly related to the text. One exception is the early fifteenth century Darmstadt Haggadah, which has a minimal amount of illustrations of the text and customs, and contains no biblical scenes at all.

The last group is that of the Italian Haggadot, whose ornamentation probably became established before the others and also served as a model for the Sephardi and Ashkenazi types. The earliest Haggadot from this cultural area, however, date from a later period (fifteenth century). The migration of German Jews to Italy gave rise to a new type of Italian-German Haggadah with Italian style illustrations but a text structure and a graphic form of letters that were based on the German model.

The first known printed version of the Haggadah was produced in 1482, in Guadalajara, Spain. Until that time, the Haggadah was part of the Siddur in the Pesah liturgy (e.g., the fourteenth century Mahzor Roma and the Sidorello, published by Soncino in 1486).

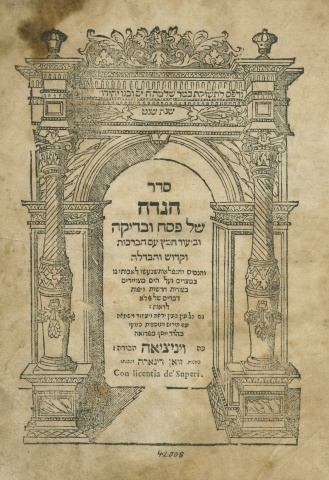

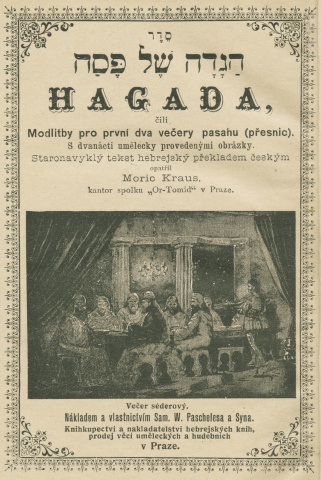

Four printed versions were published in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, whose ornamentation and graphic layout fundamentally influenced the printed form of the Haggadah. The first of these is the Prague Haggadah of Gershom ben Sholem Ha-Kohen (1526), which is ranked among the most beautiful books printed in the Renaissance. The artistic adornment of this edition for many years influenced the visual style of Haggadot in the Ashkenazi area and elsewhere. Other important editions were published by Hebrew printing houses in Mantua (1560), Venice (1609) and Amsterdam (1695). Illustrations from the Amsterdam edition, in particular, were often subsequently imitated, if not directly copied, as is evident from Haggadot published in Frankfurt (1710, 1775), Offenbach (1721) and Amsterdam (1765, 1781).

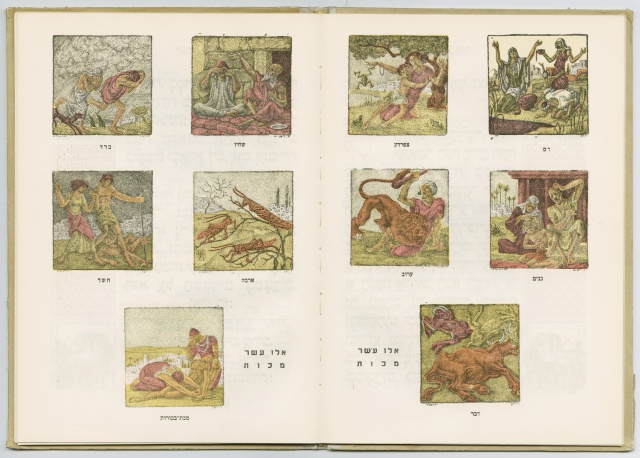

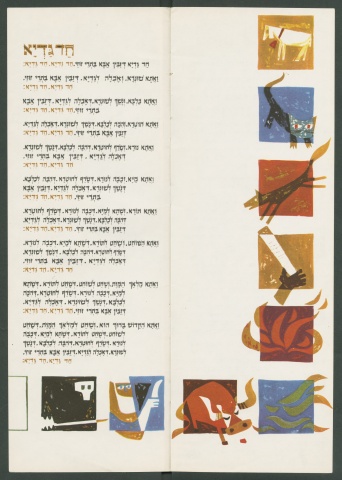

Haggadah illustrations are closely linked to the content of the text and most frequently depict the seder ceremony, biblical passages (such as the finding of Moses, slavery in Egypt, the Ten Plagues of Egypt, the Exodus from Egypt, the Red Sea crossing, etc.) and Talmudic stories that are included in the Haggadah (such as the Pesah Seder in Bnei Brak, a depiction of the Four Sons). The story of the seder song Had Gadya (One Little Goat) is also popularly depicted. This song, which is traditionally interpreted in an eschatological sense, became established as part of the Haggadah between 1526 (when the first Prague Haggadah was published, without the song) and 1590 (when the song was printed in the form that we are familiar with from later editions). Also included are eschatological hopes for a new exodus of Israel, this time from exile, as represented by the newly built Temple in Jerusalem.

Whether the illustrations relate to the distant past (the stories of the Bible and the Talmud) or to the present day, they always reflect the period of their origin. In Renaissance books, for example, figures are dressed in period clothing, and death – as can be seen in the illustrations for the Had Gadya song – is portrayed using the Christian symbolism of a skeleton with a scythe, rather than an angel. More recent editions of the Haggadah make full use of the work of contemporary Jewish artists, a trend that continued from the nineteenth century into the twentieth.

The only Haggadah published so far in the Czech Republic since the fall of Communism is the New Prague Pesah Haggadah, which is translated with a commentary by Rabbi Ephraim K. Sidon, 1996)

More than 2,700 various Haggadot have been published since the first printed edition. The Jewish Museum in Prague oversees as many as 350 Haggadot from various areas and periods. Haggadah manuscripts from Moravia, dating from the first half of the eighteenth century, and from Slovakia, dating from the first half of the nineteenth century, are among its rarest, while the 1599 Venice and 1695 Amsterdam editions are among the oldest in the museum’s collections. The museum’s collection of Pesah Haggadot not only forms a homogenous whole that charts the history, development and changes in their literary and aesthetic form, but also constitutes evidence of the diverse religious and cultural life of Czech and European Jewry.

| Wednesday 14 April, 5 p.m. | Guided exhibition tours |

| Sunday 23 May, 4 p.m. | Guided exhibition tours |

| Thursday 17 June, 5 p.m. | Guided exhibition tours |

In Czech. To organize a guided tour in English, please contact Noemi Holeková at noemi.holekova@jewishmuseum.cz

Partners

Czech Radio, City of Praguea

![[subpage-banner/3_Programavzdelavani_3.jpg]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/subpage-banner/3_Programavzdelavani_3.jpg)

![[design/2013/Twitter.png]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/design/2013/Twitter.png)

![[design/2013/Instagram.png]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/design/2013/Instagram.png)

![[homepage-banner/incident.jpeg]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/homepage-banner/incident.jpeg)