Jaroslav Róna – Parables. A selection of works, 1999 – 2008

From 29. 01. 2009 to 10. 05. 2009

open every day except for Saturdays and Jewish holidays

from 29 January until 27 March 9 a.m. – 4.30 p.m.,

from 29 March until 10 May 9 a.m. – 6 p.m

Robert Guttmann Gallery, U Staré školy 3, Praha 1

"The Enigma of Róna’s Paintings The themes of Róna’s paintings cover a vast expanse, from the origin of worlds and ancient cultures to distant cosmic civilisations. "

The Enigma of Róna’s Paintings

The themes of Róna’s paintings cover a vast expanse, from the origin of worlds and ancient cultures to distant cosmic civilisations. Other paintings remind us of scenes from contemporary science-fiction films. In fact, however, they are the fruit of the artist’s tireless imagination, fascinated by some chance object, scene or emotion, for which it seeks expression. Róna’s paintings often evolve from specific artefacts of primeval cultures and civilisations. Their subjects are obscure motifs of uncertain purpose and origin. Elsewhere they present landscapes, the prehistoric settlements of a vanished civilisation, the remains of ancient cultural edifices or the mega-cities of the present. It is not the painter’s intention that we decipher the narrative at which he hints. Rather, he is interested in something else. He wants to awaken a new experience in us, to fascinate us with his riddles and tales. All of his paintings and sculptures seem to convey some urgent message, the content of which, however, has been forgotten over the centuries. We try to assemble the original texts from their fragments and vague traces. We are attracted by their enigma. We try to puzzle them out and discover the missing connection. The content of the message, however, can be interpreted in various ways. The paintings work with fragments, allusions and suggestions, set in dark landscapes of the colours of sleep, unconsciousness and dreams.

The Discovery of Myth and ‘Bad Painting‘

In the mid 1980s, a new generation began to appear on the scene of the Prague Confrontation exhibitions. It was not bound by the developments of preceding years and was unwilling to adapt to the demands of the system or to tradition. The artwork of this generation was affected by a new artistic movement known as ‘neo-expressionism’, or ‘new’ or ‘bad painting’, which suddenly expanded the possibilities of artistic expression to include almost unlimited new techniques, materials and themes. In 1987 Róna co-founded the Tvrdohlaví (The Stubborn Ones) group, which appeared in public for the first time at the turn of 1987–1988 at the House of the People in Vysočany, and later in a series of underground exhibitions, which were perceived as an open protest against the official cultural institutions of that time. The work of the Tvrdohlaví artists demonstrated most vividly the arrival of postmodernism in Czechoslovakia. At the same time, they explored many new aspects of artistic development.

At his first solo show in the corridor of the Macromolecular Institute, Róna exhibited a large set of paintings on the theme of the mythical prehistory of the world, with motifs of primeval monsters, alone in barren, lunar landscapes, menacing creatures that bore the stigma of their own doom. It was the discovery of a myth, of the mythical experience of the world, which most of us know without being aware of it. On the local scene, these fascinating themes of monstrosity were something new. Róna’s work also restored the impact of the picture and the tradition of painting, applied in thick layers and the deep tones of the Old Masters. In 1986, he began to use the old technique of wax-painting, perhaps to get even closer to the themes of his paintings.

The 1990s

At the turn of the 1980s and 1990s, Róna grew more interested in Christian mythology and antiquity. He made paintings based on objective motifs, often in a profound and dynamic space, in deep, rich tones of colour. Classical themes appeared in paintings that showed the last crisis of the communist regime as analogous to the fall of the Roman Empire. In the early 1990s, Róna began to focus to a much greater extent on sculpture. From the beginning, his sculptural work was unusually free, developing from a neo-cubist style to machinism and the art deco of the 1920s. Gradually, however, he came to concentrate on simple, compact objects mostly cast in bronze. These resemble structures of unknown origin, models and plans of fortresses, tombs and ritual buildings. Among his best sculptural works of this period are the monumental bronze Knight and Dragon (1995) and Cuttlefish (2000) for the Klenová Chateau near Klatovy. In 2001, Róna won first prize in the competition for the monument to the writer Franz Kafka. It was completed and installed in front of one of the buildings of the Prague Jewish Museum in 2003 and won the Grand Prix of the Czech Association of Architects.

Róna’s drawings are also an inseparable component of his painting and sculptural work, the indispensable means of recording, seeking and formulating new motifs and ideas. When he began to concentrate more on sculpture, to a certain extent drawing became a substitute for painting. At that time, in a period of personal crisis, he started to make a series of ‘wilful drawings’ in a small notebook as he travelled over the Scottish highlands with their black lakes, over the dry plains of Spain and the volcanoes of Mexico. In 2002, Róna published almost 100 of his ‘wilful drawings’ from that period in a book of the same name, with texts in which he tried to express his feelings at the moment of inspiration and during and after the process of creation.

Parables of the Contemporary World

In the second half of the 1990s, there was a certain calm in Róna’s paintings. The surface of the painting gradually became consolidated and one even saw there human figures who told tales. It seems that the artist was going through a period of classicism, of sorts, which required a unity of space, time and action. He returned to old mythological themes. The paintings, however, were no longer so dramatically pointed. There was more reflection and dreaming in them. One saw there a mythical ship of death, a prehistoric ceremony of the burial of ancestors, a Mexican idol of a sinister child (Galley 1999, Ceremony 2002, Demon 2000). The Blue Monkey (2003), fleeing from a burning jungle, tells a tale of fear and a will to live. The painting When it Happened (2002) depicts an invasion from outer space. The sunken ships in the inlet and the ruins of the city on the banks, however, recall Pearl Harbour and the New York twin towers after the attacks of 11 September 2001, which clearly inspired the painting.

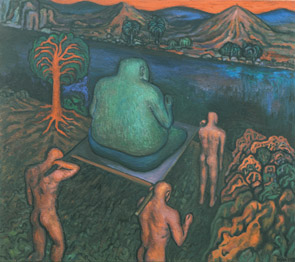

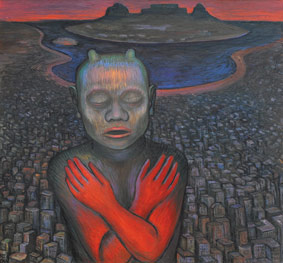

Most of the paintings at the exhibition, however, were made in the last two years, which constitute a new period in Róna’s work. At the beginning of this period is the large painting The Story of a Fat Man (2007), which illustrates Kafka’s dream from his short story ‘Description of a Struggle’. The fat man, carried on a stretcher, converses with the surrounding landscape like Buddha. He merges with nature, finally drowning in a river. The timeless themes remain the same, constantly reflecting on the human world and the universe, on its origin and the probable end that awaits us. A rather gloomy vision of contemporary civilisation, however, with endless agglomerations of skyscrapers crowding the horizon, predominates. These pictures are painted in dark blue and purple shades, which create a suggestive harmony of colours. Their dark tone, however, does not augur well. Destiny of a City (2008) shows us an adolescent devil, the personification of the collective soul of a city, dreaming the last dream of a mega-city on the shore of an ocean. Pool (2008), a parable of a totalitarian system, depicts a dark, closed space with a pool of thick, oily liquid and naked, human figures in cubicles. No one, however, bathes (the painting unwittingly recalls the pool in Godard’s film Alphaville).

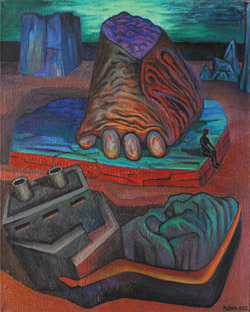

The colourful, superb painting Sodom (2008) shows the destruction of the biblical city near the Dead Sea, which was ruined in a storm of brimstone and fire regardless of the entreaties of Abraham. The remains of a fortification on a cliff and a burning fort in the background of the painting Somewhere in the East (2008) recall the recent and current conflicts in the landscapes of the deserted Eastern Bloc. The theme of catastrophe also informs the painting Anger of the Gods (2008), depicting the ruin of an ancient civilisation in a flood of glowing lava. Despite the dramatic vision, the painting, with its distinct, flat background, looks unusually decorative. Róna also returned to his favourite theme of the archaeology of extinct civilisations in the painting Landscape with a Shipwreck (2008). The atmosphere and colour of the painting recall the metaphysical paintings of Giorgio de Chirico. The shipwreck in the foreground and the fragment of an enormous elephant foot on a pedestal, with a resting pilgrim, evoke a dream of lost Atlantis.

Róna’s wealth of inspiration draws on, among other things, the world of biblical myths and Jewish history, a world that has been, over the centuries, a rich reservoir for almost all of the visions of European art about human life from its very inception. In addition to the oldest myths of human history, Róna’s work has also been affected by the tempestuous visions of the prophets, which vividly depict imminent catastrophes. The bronze figure Adam (2003), with a snake in one hand and an apple in the other, represents a rather unusual interpretation of the biblical myth. Diverging from the biblical story, Róna’s Adam does not bite the apple. His eyes remain closed and he continues to dream. The painting of the same name (2004), depicting a solitary Adam on a sea cliff with a pack of wild beasts, face to face with the incipient desolation of the earth, is a parable of the isolation of the individual in the universe. Garden of Eden (2005) shows the transformation of the biblical paradise into an infinite labyrinth of closed cells with withered trees and wild beasts, at the centre of which is a forgotten ancestral grave.

Róna’s personal, family history also includes the experience of the Shoah, which is recalled in particular in the painting Yellow Smoke (2001), dedicated to the memory of Auschwitz. This experience probably informs many of his paintings and is reflected in his dark interpretation of the world and visions of catastrophe. The painting Family Portrait (2007) shows a kneeling woman with a dog at the bank of a river, beyond which the domes of concrete underground bunkers rise from the earth. A heap of skulls lies in front of her, a cruel symbol of the murdered family. The painting Great Incinerator (2008) is a parable of all the self-destructive tendencies of modern civilisation. It depicts an enormous incinerator, which turns everything to ashes and smoke, in the middle of a mega-city of skyscrapers.

Memories of the Future

What is it really like, this world of Róna’s that is so protean and elusive? One way or another, it is unusually lively and striking. In it, the most diverse sources and forms of European artistic and literary romanticism and symbolism are intertwined. Yet it also has its own themes and motifs, from those that are unique to those that continually return with a kind of wilfulness in the same or altered form in his drawings and paintings. Some themes appear to be simple, while others capture the complex story of ruin and birth, tales of human life as part of the drama of earth and the universe. One cannot separate his work from these contexts, nor can one rid it of the inner tension and unease that give it life and constantly renew it. Twenty years ago, the Czech public, after a decades-long fast of the imagination, was fascinated by Róna’s artistic world and the possibilities it suggested of direct experience of artwork. Today, his paintings no longer strike us as novel, yet they are as fascinating as ever.

| 7 April, 2009 at 4 p.m. | Guided exhibition tours |

| 6 May 2009 at 4 p.m. | Guided exhibition tours |

![[subpage-banner/3_Programavzdelavani_3.jpg]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/subpage-banner/3_Programavzdelavani_3.jpg)

![[design/2013/Twitter.png]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/design/2013/Twitter.png)

![[design/2013/Instagram.png]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/design/2013/Instagram.png)

![[homepage-banner/incident.jpeg]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/homepage-banner/incident.jpeg)