Jarmila Mařanová. Kafka and Prague

From 25. 09. 2008 to 04. 01. 2009

open every day except for Saturdays and Jewish holidays

from 25 September until 24 October 2008 from 9 a.m. till 6 p.m.;

from 26 October 2008 until 4 January 2009 from 9 a.m. till 4.30 p.m.

Robert Guttmann Gallery, U Staré školy 3

Mařanová was one of the first Czech artists who began to focus on the Jewish victims of the Holocaust in their work. She was also probably the only Czech artist to deal systematically and to such a scale with the works of Kafka.

GRAPHIC ARTIST JARMILA MAŘANOVÁ

Jarmila Mařanová was born on 8 September 1922 in Vyšehrad, Prague. Her father, Augustin Bartoš, was a leading Czech pedagogue and director of the Jedlička Institute. Her mother Bedřiška (neé Weinberger) was a pianist and music teacher and the elder sister of composer Jaromír Weinberger. In 1925–26 the latter composed the opera Švanda the Bagpiper, which successfully premiered at Prague’s National Theatre in April 1927 and was then performed at the world’s leading opera houses. With her family background Jarmila Mařanová was destined for a music career, but fate brought her to art. Her parents divorced before the war, as a result of which her mother was deported to the Terezín ghetto in 1942. Her mother and grandmother both perished in the Treblinka death camp. During the Nazi occupation, Jarmila Mařanová attended Prague’s School of Decorative Arts, studying textile and glass design. Graduating in 1944, she began to focus on book and poster design after the war. She married Jaroslav Mařan, with whom she had two children, Ilja and Evička. In 1956–58 she contributed to the interior design of the Czechoslovak Pavilion for the World Expo in Brussels and exhibited with a group of designers at the Umělecká beseda in Prague.

DISTANT JOURNEY

Mařanová’s first major independent work was a set of graphic studies and paintings that were dedicated to the memory of her mother. These works date from the late 50s, when she was trying to come to terms with her trauma. Her Holocaust-related artwork was inspired mainly by the fate of her family and friends who perished in Nazi death camps. Her studies and paintings provide a poetic metaphor for the deep sorrow at the loss of loved ones and still retain their power. Some depict the Terezín ghetto and the fate of her cousin and other children who were incarcerated there. The coloured linocut Střelnice (1961) recalls the anti-Semitism of folk puppet theatre by showing Jewish faces as targets at a fair shooting range. Her main achievement is To the Victims of the Warsaw Ghetto (1963), a large painting that depicts the ardent faces of the brave ghetto fighters as apparitions in the flames in front of the ghetto walls. These works were featured in Mařanová’s first one-person show for the 20th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, which was held at the Czechoslovak Cultural Centre in Warsaw in April 1963. She returned to this topic only many years later in America, when she made a new portrait of her mother and grandma.

KAFKA AND PRAGUE

Interest in Kafka began to spread after the war also in Czechoslovakia. New translations appeared, a Czech edition of his works was planned, and the first collection of Kafka-related studies and memoirs was published. Such work was pushed into the background after February 1948 but quickly revived during the political easing after 1956. Eisner’s translation of The Trial was published in 1958, starting a new wave of interest in Kafka’s work in the Czech lands. This culminated in an international conference on Kafka at Libice near Prague in 1963 – the 80th anniversary of Kafka’s birth. A year later, to mark the 40th anniversary of Kafka’s death, the Museum of Czech Literature hosted the exhibition Franz Kafka – Life and Work; Max Brod attended and gave a speech at the opening show on 23 June 1964. In addition to documents and books, the exhibition also presented the work of a number of young and unofficial artists who offered surprising parallels with the style, motifs and atmosphere of Kafka’s writings.

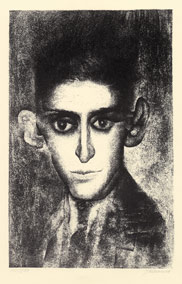

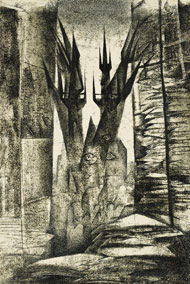

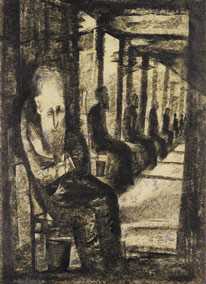

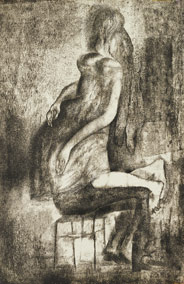

Everything seemed to recall Kafka in the Prague of the early 1960s – the unreal atmosphere of a crumbling city, the outright absurdity of everyday life and the poorly functioning bureaucratic system. Mařanová also turned her attention to the literary work of Kafka at this time. As she later said, she was close to Kafka for two reasons: “First of all, Kafka looked like one of my cousins, and secondly my reading of his works reminded me so much of the atmosphere of the pre-war Jewish Town, where I used to walk with my grandma Weinberger, mother and sister...”Her monotypes are only in part illustrations of certain scenes in Kafka’s short stories and novels; mostly they are a loosely based graphic accompaniment or paraphrase of the feelings and thoughts provoked by his work. She adds: “Franz Kafka corresponds to my own inner dream world. I feel at home in the atmosphere of Kafka’s prose, although it affects me intuitively rather than rationally. His state of mind is close to me – as is his home town…”

Mařanová transforms Kafka’s existentially tinged stories into images that compellingly evoke the atmosphere of old Prague. The surface of Mařanová’s monotypes forms a structure that is reminiscent of the walls of old buildings, from which hidden images and indistinct faces suddenly emerge. She creates ghostly figures that languidly move as if in delirium or hover over the city as if in a dream, lending a highly imaginative and surrealistic quality to her paintings.

Mařanová also made separate monotypes for the short stories A Country Doctor, Trapeze Artist and A Hunger Artist, for Kafka’s letters to Milena and for several of his aphorisms. As mentioned by Ludvík Aškenázy at her Vienna exhibition in February 1967: “Two Prague walkers – Franz Kafka and Jarmila Mařanová – met. They missed each other in space, either on purpose or by mistake. But they did meet each other in time, where the two found themselves without having to exchange a single word. Neither of Jarmila Mařanová’s cycles, Kafka’s Prague and Kafka’s The Trial, are mere illustrations. They are a greeting from the realm of anxiety and darkness. A record of a new walk through the old, winding lanes of life in which a distant, solitary window with the silhouette of a person sometimes opens.”

Mařanová followed on from her Kafka series with 12 lithographs for Woyzeck, Büchner’s play about the tragic fate of a man unable to deal with the cold-hearted indifference of the external world. Büchner’s style has much in common with Kafka; his irony stretches to grotesquery and an acutely realistic vision is mingled with dream-like hallucinations.

BIBLICAL MOTIFS

In an atmosphere of disappointment and hopelessness after the occupation of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, when her children emigrated to the USA, Mařanová found a corresponding theme for a new series of prints in the Book of Job. To her, Job’s fate projects an image of human existence; his ordeals convey a picture of deepest despair and an archetype of all human tragedy. In 1969 she made a number of lithographs and monotypes for the series; these were put on display at the Spanish Synagogue in the Jewish Museum in Prague in 1970. In marked contrast is a set of lithographs for the most poetic book of the Old Testament, Solomon’s Song of Songs, dating from 1973–74. Mařanová describes in them the unique character of the Israeli landscape as she remembered it from her visit to Israel in 1968.

In the early years of normalization, Mařanová found inspiration in The Labyrinth of the World and the Paradise of the Heart, written in 1623 by a young John Amos Comenius (1592–1670) in a similarly hopeless political situation – two years following the Battle of White Mountain and after the executions of Czech nobles; Comenius was on the run, shortly after the death of his first wife and first-born son. In a large series of about 30 lithographs from 1972–73, Mařanová uncovers the drama of the alienated and hostile world of incipient normalization, but also discovers the figure of the pilgrim, an outcast from his own country, which was soon to become her fate, too.

AMERICA AND THE CASTLE

In 1976 Mařanová went to the U.S. to be with her children. After two years in Los Angeles, she then moved to New York, where she lived until 2005. Amid the labyrinth of skyscrapers she returned once again to Kafka. In 1977–78 she made another series of monotypes, this time for Kafka’s novel America. It was a difficult experience for Mařanová, encountering a completely different and alien world, and it was in Kafka’s America she found a description of a traumatic encounter with the New World – the arrival of young Karl Rossmann from Prague. Later on, she started to focus on motifs from Kafka’s The Castle, which also describes the feelings and situations of a person in an alien and incomprehensible world – the land surveyor K. Drawing upon a lifelong preoccupation with Kafka, she drew the illustrations for a bibliophile edition of The Trial and The Castle (published by the Franklin Library, Philadelphia), for which in 1984 she received four awards from leading American graphic design and art associations.

In her last, unfinished series, the central motifs from Kafka and Comenius are combined in the symbolic figure of a Jewish pilgrim, an outcast restlessly wandering through worlds and centuries with a pack on his back and a Torah scroll in his arms. Also appearing more frequently in her paintings are Prague clocks with numbers in Hebrew, running backward as if deeper and deeper into the past to the beginnings of Creation. Mařanová is returning more and more to the Prague sources of her inspiration, too.

RETURN TO PRAGUE

Mařanová was one of the first Czech artists who began to focus on the Jewish victims of the Holocaust in their work. She was also probably the only Czech artist to deal systematically and to such a scale with the works of Kafka. In 1993, the Jewish Museum presented a large collection of her work from the U.S. In 1995 she contributed to the exhibition Old Testament Motifs in 20th Century Czech Art in Roudnice nad Labem Gallery. In 2006 she gave the Jewish Museum a collection of 54 of her earliest and most successful monotypes and lithographs, inspired by the works of Franz Kafka. Dating mostly from 1963–67, this work was shown first at the Jewish Museum in 1965 and then across Europe and the U.S. Her series of Kafka-inspired work belong up to the present day among the best artworks of its kind.

![[subpage-banner/3_Programavzdelavani_3.jpg]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/subpage-banner/3_Programavzdelavani_3.jpg)

![[design/2013/Twitter.png]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/design/2013/Twitter.png)

![[design/2013/Instagram.png]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/design/2013/Instagram.png)

![[homepage-banner/incident.jpeg]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/homepage-banner/incident.jpeg)