CINEGOGUE

MUSIC / FILM / ARCHITECTURE

CINEGOGUE is a series that combines “cinema” with “synagogue” to screen silent films accompanied by live music in a historic space acclaimed for its architecture. Its mission is to uncover little known works of world cinematography to present a different view of Jewish culture and the artists of the post-emancipation period, which saw not only the inception of the international Zionist movement and the large waves of immigration from Central and Eastern Europe to the New World, but the frenetic growth of the avant-garde and cinema as well.

The premieres are annually held in the Spanish Synagogue, built in the Moorish Revival style in 1868. The most stunning of

all Prague synagogues, it was long the natural spiritual center of the city’s German-speaking Jews. Its interior design

from the 1880s brings to mind a luxurious theater or the charm of a nickelodeon, and interestingly enough, it was built around

the same time, and perhaps for similar reasons, as the National Theater in Prague, a quasi-sacred structure that embodied

the national identity and cultural emancipation of Czechs.

The premieres are annually held in the Spanish Synagogue, built in the Moorish Revival style in 1868. The most stunning of

all Prague synagogues, it was long the natural spiritual center of the city’s German-speaking Jews. Its interior design

from the 1880s brings to mind a luxurious theater or the charm of a nickelodeon, and interestingly enough, it was built around

the same time, and perhaps for similar reasons, as the National Theater in Prague, a quasi-sacred structure that embodied

the national identity and cultural emancipation of Czechs.

Thanks to the synagogue’s acoustic qualities, these gems from internationally important film archives are always accompanied

by music from leading composers and performed live by outstanding musicians. When the original or reconstructed score still

exists, and it is possible to synchronize it with the preserved copy of the film, then it is performed live. If the original

score has not survived, then a new one is composed specially for the occasion.

CINEGOGUE has become a fixture of the Jewish Museum in Prague’s fall program. The series is conceived and organized by Michaela Sidenberg, the Museum’s visual arts curator. For the most part, Cinegogue's musical dramaturgy is managed by Peter Vrabel, the chief conductor of Berg Orchestra.

Cinegogue - Archives of previous years

2016-The Second Sex: Tilly Losch, Stella Simon, Maya Deren

09 + 10 / 10 / 2016

Spanish synagogue

Cinegogue 2015 is organized in collaboration with the Berg Orchestra.

Cinegogue 2016 turns its attention to Jewish female artists and protagonists who left an indelible mark not only in the realm

of experimental cinematography but also in the realms of photography (Stella F. Simon, Maya Deren), dance (Tilly Losch, Maya

Deren), and film theory (Maya Deren). In this eighth year of the Cinegogue program we go for the first time beyond 1929, considered

the definitive end of the silent era, to present short films that were intentionally shot as silent experiments focused exclusively

on cinematic language. All the films will be accompanied by new scores specially composed for the program and performed by

Berg Orchestra and arranged by its artistic director and conductor Peter Vrábel.

Program brochure

Stella F. Simon (1878-1973), Miklós Bándy (1904-1971)

Hände: Das Leben und die Liebe eines zärtlichen Geschlechts / Hands: The Life and Loves of the Gentler Sex / Ruce: Život

a lásky něžného pohlaví

1927-28, USA, 13 min.

Music: Tomáš Reindl

Stella F. Simon (1878-1971)

At the age of eight Stella Furchgott moved with her family from her native Charleston, South Carolina, to Colorado. Her creative

inclinations took root during high school in Denver and she took up musical composition. A few years after graduating, she

married the merchant Adolph Simon and moved to his home city of Salt Lake City, Utah. Adolph died in 1917, and Stella’s

life slowly began to veer in a somewhat unconventional direction, particularly given the norms of that era. A widow and mother

of three sons, she moved to New York in 1923 and began to study at the private school of the renowned American pictorialist

photographer Clarance Hudson White. When he died suddenly in 1925, her plans changed once again. She decided to study film,

and in 1925 traveled to Berlin where she attended the Technische Hoschschule. She met the pioneer of experimental film Hans

Richter at UFA studios, and he makes a cameo appearance in her four-minute film composition simply titled Filmstudie (1926).

While in Berlin she shot her only full-length film, Hände: Das Leben und die Liebe eines zärtlichen Geschlechts (Hands:

The Life and Loves of the Gentler Sex). Though the narrative is built on a banal melodramatic plot of ill-fated love replete

with Hollywood happy ending, the unorthodox form of the film was inspired by contemporary avant-garde aesthetics and today

is considered one of the pioneering films in feminist Western cinematography. Once the film found success on both sides of

the Atlantic, Simon returned to New York in 1931 and opened her own photographic studio. During the Second World War she worked

as a volunteer training members of the U.S. Army Signal Corps who were tasked with creating the photo documentation of Allied

operations during the war. No longer active after the war, she lived in seclusion. In the annals of film she has remained

a single-film auteur, which was created in close cooperation with Miklós Bándy.

At the age of eight Stella Furchgott moved with her family from her native Charleston, South Carolina, to Colorado. Her creative

inclinations took root during high school in Denver and she took up musical composition. A few years after graduating, she

married the merchant Adolph Simon and moved to his home city of Salt Lake City, Utah. Adolph died in 1917, and Stella’s

life slowly began to veer in a somewhat unconventional direction, particularly given the norms of that era. A widow and mother

of three sons, she moved to New York in 1923 and began to study at the private school of the renowned American pictorialist

photographer Clarance Hudson White. When he died suddenly in 1925, her plans changed once again. She decided to study film,

and in 1925 traveled to Berlin where she attended the Technische Hoschschule. She met the pioneer of experimental film Hans

Richter at UFA studios, and he makes a cameo appearance in her four-minute film composition simply titled Filmstudie (1926).

While in Berlin she shot her only full-length film, Hände: Das Leben und die Liebe eines zärtlichen Geschlechts (Hands:

The Life and Loves of the Gentler Sex). Though the narrative is built on a banal melodramatic plot of ill-fated love replete

with Hollywood happy ending, the unorthodox form of the film was inspired by contemporary avant-garde aesthetics and today

is considered one of the pioneering films in feminist Western cinematography. Once the film found success on both sides of

the Atlantic, Simon returned to New York in 1931 and opened her own photographic studio. During the Second World War she worked

as a volunteer training members of the U.S. Army Signal Corps who were tasked with creating the photo documentation of Allied

operations during the war. No longer active after the war, she lived in seclusion. In the annals of film she has remained

a single-film auteur, which was created in close cooperation with Miklós Bándy.

Tomáš Reindl

Tomáš Reindl (b. 1971) is a composer and working musician, a multi-instrumentalist and tabla player. Inspired by old European and non-European musical traditions (particularly the Middle Ages, Indian music, African polyrhythms, etc.), his music crosses genres while at the same time utilizing modern music technology and processes. He is practically the only composer in the Czech Republic who incorporates Indian rhythms. He learned how to play the tabla under Sanjay Sahair, one of the leading contemporary masters of the instrument. He studied composition at the Music and Dance Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (HAMU) under Prof. Hanuš Bartoň, as well as taking a number of courses, workshops, and private lessons. He teaches ethnomusicology at HAMU while regularly performing his solo project OMNION and collaborating with many artists and ensembles in the Czech Republic and abroad.

When composing the music to this film I wanted first and foremost to shift how the story on the screen is perceived, which

despite its very original visual approach is marked by a hint of naiveté. As for crafting the composition, I would point

to my systematic work with melodic motifs (or leitmotifs if you will), which are solely five-toned, since, as we are aware,

the vast majority of human hands (such as that of the film’s lead actor) have five fingers...

Norman Bel Geddes (1893-1958), Tilly Losch (1903-1975)

Dance of Hands / Tanec rukou

1930-33, USA, 7 min.

Hudba: Michaela Pálka Plachká

Tilly Losch (1903-1975)

Dancer, choreographer, actress, and amateur painter, Ottilie Ethel Leopoldine Herbert, Countess of Carnarvon, was born Ottilie Ethel Losch to a Jewish family in Vienna. Her career and life resembles more a novel whose protagonist is a femme fatale and all that comes with it: adulation, sudden outbursts, love affairs, peaks and valleys. From the age of six Losch studied ballet at the Vienna Opera, becoming nine years later a permanent member of the Opera’s corps de ballet and in 1921 a coryphée. At this time Losch was also appearing in productions outside the Opera, which she left for good in 1927 to more closely collaborate with the already renowned theater director Max Reinhardt. She was not only a dancer and choreographer in his productions, but also an actress. After leaving her permanent engagement at the Opera she appeared in the major cities of Europe and in New York (dancing on Broadway with Fred Astaire among others) and collaborated with a host of eminent directors, composers, choreographers, and musicians. In 1933, George Ballanchine, whom she had met a decade earlier, choreographed for her the “sung ballet” The Seven Deadly Sins composed by Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht. This unconventional piece that called for a “double” lead – a dancer and a singer – was commissioned by Losch’s current husband, the prominent British patron of Surrealism Edward James. Her marriage to James did not last long, however, and mad love turned into a contentious divorce, after which Losch fell into a deep depression. She ended her career as a dancer and, secluded in a Swiss sanatorium, began to paint. At this time she met her second husband, Henry Herbert, 6th Earl of Carnarvon. Alarmed by the worsening situation in Europe, he sent Losch to the United States, where she continued to paint, mounting her first exhibition in 1944 in New York. Her second marriage was also destined to be short-lived, and it ended in 1947. Losch spent the remaining years of her life commuting between New York and London. She died of cancer on December 24, 1975, in New York.

At the height of her independent dance career Losch shot the short film Dance of the Hands in collaboration with the American scenic and industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes. It might seem like no more than a marginal episode in the dizzying artistic career of Tilly Losch, who appeared as well in rather well-known Hollywood and European feature films. Yet it captures the essence of her dance expression and how she viewed herself, as she laconically summed up: “My role of ballerina comes first. Second is my work as a choreographer. My acting comes third, my painting fourth, I rate my role as Lady Carnarvon fifth in importance simply because I can’t think of anything interesting to put after painting …”

Michaela Pálka Plachká

Michaela Pálka Plachká (b. 1981) draws inspiration from literature and fine arts for her compositions. But the most powerful inspirations are people of flesh and bone, their stories, thoughts, and experiences. The various paradoxes and contrasts of a life are recast in musical form, each composition having its specific aspects. Her work has been enriched in interesting ways of late through working with people, their energy, the perception of the multifaceted dimensions of the world and being, and the cyclical nature of life. At present she is exploring sound installation as part of her postgraduate studies. A member of the composers’ association Konvergence, she now lives and works in Germany.

This poetic film captures not only a “dance of hands” but also the dance of the entire body of Tilly Losch. The choreography of the movements develop gradually, evoking a story that while indefinite can be filled in by one’s own imagination. The film transported me to the world of plants, their hidden movements that many times are barely discernible by the naked eye, yet when shot on video and sped up they become perceptible. During the entire time I was composing new music for this film from 1933 I intentionally did not listen to the original score. I will wait until after the premiere to compare the two.

Maya Deren (1917-1961), Alexander Hammid (1907-2004)

Meshes of the Afternoon / Odpolední osidla

1943, USA, 14 min.

Hudba: Jiří Lukeš

Maya Deren (1917-1961)

Maya Deren was born in Kiev as Eleanora Derenkowsky in the revolutionary year of 1917. At the age of five her family immigrated

to the United States to escape the pogroms and anti-Semitism then sweeping the Ukraine. In 1928, the family became naturalized

and changed their surname to Deren. Coming from a family of intellectuals (her father, Dr. Salomon Drenkowsky, was a psychoanalyst

who graduated from the Moscow Psychoneurological Institute) the multitalented Eleanora wrote poetry from a very young age.

She matriculated at Syracuse University, married for the first time, soon got divorced, moved to New York City, worked as

a secretary for the Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL), and continued her education at New York University, earning

a BA, and Smith College, receiving a master’s degree in English literature in 1939. After graduating, Deren took a position

as an assistant to Afro-American dancer and choreographer Katherine Dunham and accompanied her on performance tours across

the United States. On a trip to Los Angeles in 1941 she met a young émigré from Prague, the filmmaker Alexander Hammid (born

Hackenschmied), whom she soon married and changed her name to Maya (the Hindu expression for “illusion”). In 1943, she

and Hammid shot the short film Meshes of the Afternoon. The couple lived in New York’s Greenwich Village, the center of

the city’s intellectual life and where Deren met many of the European émigrés and American artists who would soon appear

in and collaborate on her films (Anaïs Nin, Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, Gore Vidal et al.). Deren wrote, photographed, and

even received some renown for her original fashion creations. She also shot more short films: Witch’s Cradle (1944); At

Land (1944); A Study in Choreography for Camera (1945); Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946). She rented the Provincetown Playhouse

at her own expense to show her films, and this directly inspired Amos Vogel, a leading American film theorist and promoter

of experimental cinema, to found the ciné-club Cinema 16, which in the 1950s became the most successful American film association

screening independent cinema (members included Arthur Miller and Dylan Thomas). In 1946, Deren received her first Guggenheim

Fellowship and wrote and published a theoretical essay on film, An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film, in which she formulated

the principles of her poetic vision. The structure of Deren’s own aesthetic canon where the poetics of the work (vertical)

takes precedence over plot (horizontal) is often compared to the propositions of structural linguist Roman Jakobson. She conceived

the ideal work of art (that is, including film) as being a result of collectively performed ritual, not the fetishization

of icons based on the individual psyches of their creators. Deren single-mindedly pursued her own path while rejecting any

connection to Surrealism, psychoanalysis, and documentary film. She considered Surrealism a navel-gazing eccentricity and

documentary film as an insufficiently creative endeavor. In later films she tried to take an approach that would be consistent

with these principles, and this put her work at odds with the creative dogma of the day that placed emphasis on the new mode

of government supported abstract expressionism or the increasingly fashionable use of the indifferent observation technique

of cinema verité. Deren published Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti in 1953 in which she summarized her long interest

in dance, magic, and ritual. Often compared to Sergei Eisenstein’s unfinished ¡Que viva México! from the early 1930s in

terms of importance and scope, Deren shot many hours of film footage on Haitian Vodou yet did not manage to edit it down to

final feature length during her life. A filmmaking legend that one critic likened to “a cinematic Prometheus stealing the

fire of the Hollywood gods,” Deren died prematurely in 1961 of entirely earthly causes – a brain hemorrhage evidently

brought on from her longtime dependence on barbiturates and amphetamines.

Maya Deren was born in Kiev as Eleanora Derenkowsky in the revolutionary year of 1917. At the age of five her family immigrated

to the United States to escape the pogroms and anti-Semitism then sweeping the Ukraine. In 1928, the family became naturalized

and changed their surname to Deren. Coming from a family of intellectuals (her father, Dr. Salomon Drenkowsky, was a psychoanalyst

who graduated from the Moscow Psychoneurological Institute) the multitalented Eleanora wrote poetry from a very young age.

She matriculated at Syracuse University, married for the first time, soon got divorced, moved to New York City, worked as

a secretary for the Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL), and continued her education at New York University, earning

a BA, and Smith College, receiving a master’s degree in English literature in 1939. After graduating, Deren took a position

as an assistant to Afro-American dancer and choreographer Katherine Dunham and accompanied her on performance tours across

the United States. On a trip to Los Angeles in 1941 she met a young émigré from Prague, the filmmaker Alexander Hammid (born

Hackenschmied), whom she soon married and changed her name to Maya (the Hindu expression for “illusion”). In 1943, she

and Hammid shot the short film Meshes of the Afternoon. The couple lived in New York’s Greenwich Village, the center of

the city’s intellectual life and where Deren met many of the European émigrés and American artists who would soon appear

in and collaborate on her films (Anaïs Nin, Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, Gore Vidal et al.). Deren wrote, photographed, and

even received some renown for her original fashion creations. She also shot more short films: Witch’s Cradle (1944); At

Land (1944); A Study in Choreography for Camera (1945); Ritual in Transfigured Time (1946). She rented the Provincetown Playhouse

at her own expense to show her films, and this directly inspired Amos Vogel, a leading American film theorist and promoter

of experimental cinema, to found the ciné-club Cinema 16, which in the 1950s became the most successful American film association

screening independent cinema (members included Arthur Miller and Dylan Thomas). In 1946, Deren received her first Guggenheim

Fellowship and wrote and published a theoretical essay on film, An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film, in which she formulated

the principles of her poetic vision. The structure of Deren’s own aesthetic canon where the poetics of the work (vertical)

takes precedence over plot (horizontal) is often compared to the propositions of structural linguist Roman Jakobson. She conceived

the ideal work of art (that is, including film) as being a result of collectively performed ritual, not the fetishization

of icons based on the individual psyches of their creators. Deren single-mindedly pursued her own path while rejecting any

connection to Surrealism, psychoanalysis, and documentary film. She considered Surrealism a navel-gazing eccentricity and

documentary film as an insufficiently creative endeavor. In later films she tried to take an approach that would be consistent

with these principles, and this put her work at odds with the creative dogma of the day that placed emphasis on the new mode

of government supported abstract expressionism or the increasingly fashionable use of the indifferent observation technique

of cinema verité. Deren published Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti in 1953 in which she summarized her long interest

in dance, magic, and ritual. Often compared to Sergei Eisenstein’s unfinished ¡Que viva México! from the early 1930s in

terms of importance and scope, Deren shot many hours of film footage on Haitian Vodou yet did not manage to edit it down to

final feature length during her life. A filmmaking legend that one critic likened to “a cinematic Prometheus stealing the

fire of the Hollywood gods,” Deren died prematurely in 1961 of entirely earthly causes – a brain hemorrhage evidently

brought on from her longtime dependence on barbiturates and amphetamines.

Jiří Lukeš

A composer and accordionist, Jiří Lukeš (b. 1985) studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Eduard Douša and

accordion under Ladislav Horák. While a student he received a number of awards in accordion competitions. He finished his

degree at HAMU in 2014 under Ivana Loudová. Lukeš is also the author of New Timbral Possibilities for the Accordion in the

Context of Contemporary Instrumentation. His compositions have been performed at concerts and at festivals in the Czech Republic,

Slovakia, Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, China, Serbia, and Ukraine. Lately he has been focused on international projects while

continuing his work as a teacher at the Prague Convervatory and the Štefánikova and Taussigova primary art schools. Since

2015 he has represented the Czech Republic in the UNESCO sanctioned organization Confédération Internationale des Accordéonistes.

A composer and accordionist, Jiří Lukeš (b. 1985) studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Eduard Douša and

accordion under Ladislav Horák. While a student he received a number of awards in accordion competitions. He finished his

degree at HAMU in 2014 under Ivana Loudová. Lukeš is also the author of New Timbral Possibilities for the Accordion in the

Context of Contemporary Instrumentation. His compositions have been performed at concerts and at festivals in the Czech Republic,

Slovakia, Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, China, Serbia, and Ukraine. Lately he has been focused on international projects while

continuing his work as a teacher at the Prague Convervatory and the Štefánikova and Taussigova primary art schools. Since

2015 he has represented the Czech Republic in the UNESCO sanctioned organization Confédération Internationale des Accordéonistes.

My main inspiration came from the Surrealist aspects of the film: the protean meaning of symbols, the merging of dream and reality, the play of light and shadow. Like the film, the music is based on repetitive and changing motifs. Despite these structural similarities, the composition remains an independent whole linked to the images only in a few places. The violoncello solo emerges from a background of live electronics processing and introduces an acoustic reflection of the silhouettes of figures appearing on the screen.

Maya Deren (1917-1961)

At Land / Zeměplavba

1944, USA, 15 min.

Hudba: Matouš Hejl

Matouš Hejl

Matouš Hejl (b. 1989) is a composer and pianist. Having attended Berklee College of Music in Boston and graduating from HAMU

in Prague, he is now a student of electroacoustic composition at the Royal College of Music in Stockholm. Electronics and

algorithmic progressions are often featured in his music. He has collaborated on a number of theater, dance, and other types

of performances (at such venues as Jatka 78, Meetfactory, Alfréd ve dvoře) and multimedia projects. His film debut, the

score for Petr Zelenka’s Lost in Munich, earned him a Czech Lion nomination for best music.

Matouš Hejl (b. 1989) is a composer and pianist. Having attended Berklee College of Music in Boston and graduating from HAMU

in Prague, he is now a student of electroacoustic composition at the Royal College of Music in Stockholm. Electronics and

algorithmic progressions are often featured in his music. He has collaborated on a number of theater, dance, and other types

of performances (at such venues as Jatka 78, Meetfactory, Alfréd ve dvoře) and multimedia projects. His film debut, the

score for Petr Zelenka’s Lost in Munich, earned him a Czech Lion nomination for best music.

The music for the film At Land for the Berg Orchestra is conceived as contrapuntal to the poetics of the original cinematic imagery. In some places the film’s poetics have been somewhat stifled by the music to create a new meaning. In each of the nine sections there are usually two minor parts: at first more static, presenting the given situation, and then proceeding through the action or situation to a more dynamic second part that ultimately becomes a bridge to the subsequent scene. The rhythm of the cinematic montage is a striking, somewhat musical element as well. My composition incorporated all this in its own way. In one of her books Maya Deren notes that film depicts a particular individual’s struggle with identity. My score is a musical complement to the film, and as an autonomous work it poses the question of the identity of a work comprising imagery and sound.

Maya Deren (1917-1961)

Ritual in Transfigured Time / Rituál v proměněném čase

1946, USA, 15 min.

Hudba: Miroslav Tóth

Miroslav Tóth

Miroslav Tóth (b. 1981), a composer and saxophonist, specializes in experimental music, musical improvisation, and audiovisual

conceptualizations. He studied saxophone and piano at the Bratislava Conservatory, musicology at Comenius University, and

composition at the Academy of Performing Arts in Bratislava. He has composed music for solo instrument, chamber ensembles,

as well as four operas (Massage Bar for Public Officers, Zub za zub, Oko za oko, and Tyč). He realized many projects with

Frutti di mare, an audiovisual group with a revolving cast of around 60 musicians who performed graphic notations improvised

by a VJ in real time. In addition to serving as the artistic director of the abstract improvisational orchestra Musica falsa

et ficta, Tóth also performs with other groups, such as Shibuya Motors, My Live Evil, the Paľko & Tóth Duo, Funeral Band,

and with the Polish bassist Rafal Mazur.

Miroslav Tóth (b. 1981), a composer and saxophonist, specializes in experimental music, musical improvisation, and audiovisual

conceptualizations. He studied saxophone and piano at the Bratislava Conservatory, musicology at Comenius University, and

composition at the Academy of Performing Arts in Bratislava. He has composed music for solo instrument, chamber ensembles,

as well as four operas (Massage Bar for Public Officers, Zub za zub, Oko za oko, and Tyč). He realized many projects with

Frutti di mare, an audiovisual group with a revolving cast of around 60 musicians who performed graphic notations improvised

by a VJ in real time. In addition to serving as the artistic director of the abstract improvisational orchestra Musica falsa

et ficta, Tóth also performs with other groups, such as Shibuya Motors, My Live Evil, the Paľko & Tóth Duo, Funeral Band,

and with the Polish bassist Rafal Mazur.

It is difficult to write about something that should remain unspoken. Analyses that attempt to do so end in catastrophe.

There is apparently a hidden alchemy in what Maya Deren wishes to convey, in the inability to verbalize what we are seeing.

I marvel at the somnolent movements in the Ritual in Transfigured Time (a corny infatuation with “body” adoration) against

a backdrop that might leave us uneasy with a vague premonition of doom.

2015-The Poetic Avant-Garde between Walt Whitman to Robert Desnos

12 + 13 / 10 / 2015

Spanish synagogue

Brochure

Cinegogue 2015 is organized in collaboration with the Berg Orchestra.

Charles Sheeler, Paul Strand

Manhatta, 1920

While it might be a bit presumptuous to call Manhatta one of the first attempts at documentary film, one could certainly agree

that it is the first film in American cinematography intentionally conceived as experimental, becoming as well the precursor

for “city films.” The main protagonist is the city of New York, a metropolis “proud and passionate” in the words of

Walt Whitman (1819–1892), excerpts of whose verse appear in the film’s intertitles. One recognizes here the poem “City

of Ships,” which was part of the originally separate volume Drum-Taps, containing poems from the time of the American Civil

War, that was later incorporated into the ever-expanding collection Leaves of Grass. Though this poem forms the textual base

for the film, it is excerpted and tailored to work symbiotically with the image.

While it might be a bit presumptuous to call Manhatta one of the first attempts at documentary film, one could certainly agree

that it is the first film in American cinematography intentionally conceived as experimental, becoming as well the precursor

for “city films.” The main protagonist is the city of New York, a metropolis “proud and passionate” in the words of

Walt Whitman (1819–1892), excerpts of whose verse appear in the film’s intertitles. One recognizes here the poem “City

of Ships,” which was part of the originally separate volume Drum-Taps, containing poems from the time of the American Civil

War, that was later incorporated into the ever-expanding collection Leaves of Grass. Though this poem forms the textual base

for the film, it is excerpted and tailored to work symbiotically with the image.

Paul Strand (1890-1976), photographer and documentary filmmaker, Strand was a leading figure among American modernist photographers. He was born in New York to Czech-Jewish immigrants. His early shots of the urban spaces of his native city attracted the attention of photography aficionados, and his famous photograph Wall Street from 1915 appears in his film Manhatta, which he made with another American modernist, the painter/photographer Charles Sheeler (1883–1965). During the Great Depression of the 1930s, Strand’s work was focused mainly on social photography and documentary film. He was one of the founders of the Photo League, a cooperative of left-leaning photographers – indeed, many of the leading American photojournalists of the day – whose mission was to bring acute social problems to the public’s attention. In 1936, he and his friend and collaborator Ralph Steiner founded Frontier Films, which similar to the Photo League sought to raise public awareness of social and political issues. Strand presented his film Native Land (1942) at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in 1949 and then stayed in Europe, living the rest of his life in the French town of Orgeval just a few kilometers northwest of Paris.

Ralph Steiner

H2O, 1929, 13’

Mechanical Principles / Zákony mechaniky, 1930

These two cinematic compositions by Ralph Steiner from the turn of the 1930s are next to Paul Strand’s work another example

of the interest American avant-garde photographers took in experimenting with the cinematic image. Having studied chemistry

before he took up photography, it should come as no surprise that Steiner titled his first film after a chemical formula.

Yet he was interested in water not as a chemical substance but as natural element endowed with uncommon properties, which

in its amorphous liquid state reacts to external influences – light, gravity, and kinetic energy – with a fascinating

play of reflections and textures, geometric patterns and effects bordering on an impeccable optical illusion. In his film

Mechanical Principles a year later, Steiner is clearly still captivated by visual abstraction, although here it is not a product

of the work of nature but of an intrinsically artificial force – the mechanical organism.

Ralph Steiner (1899-1986), an accomplished photographer, Steiner was a key figure in American progressive documentary filmmaking. He was born in Cleveland, Ohio, into a family of poor Jewish immigrants from Bohemia. He originally matriculated at Dartmouth College to study chemistry but quickly switched over to photography, which in a short time became a source of livelihood. Having moved to New York, he worked as a commercial photographer while taking a keen interest in film, which he soon began to experiment with and study. He met Paul Strand at the turn of 1927 and co-founded with him the Film and Photo League (FPL). Not long after he made his first films, H20 in1929 and Mechanical Principles in 1930. Steiner quit the FPL in 1933 and became a member of the loose association Nykino, which was a better match for his interest in film as a form of social activism. In 1936, he and Strand founded the production company Frontier Films. After a short flirtation with Hollywood, where he tried to establish himself in the 1940s as a screenwriter and producer, Steiner returned to fashion photography and photojournalism in New York (working for magazines such as Vogue and Look). He spent the last two decades of his life in Vermont, photographing the Maine seaside and shooting on a series of films on his own, which cannot be ranked, however, among his best work.

Man Ray

Emak bakia, 1926

L’étoile de mer / Mořská hvězda, 1928

The title of Man Ray’s film Emak Bakia is Basque (i.e., Euskara) for “Leave Me Alone.” Subtitled a cinépoéme, it is

an attempt to “compose” a poem through images in motion. It also refers to the house in the southern French town of Biarritz

where Man Ray spent his summers. A nineteen-minute stream of associations, the film includes shots from Ray’s first film

Le retour à la raison (Return to Reason) that was in part constructed from animation of his “rayographs” (photograms

made from the exposure of objects arranged directly on photographic paper). Although Man Ray himself claimed that Emak Bakia

was an entirely conventional composition with a linear logic, one clearly recognizes in the film the effort – common to

all dadaists and surrealists – to disrupt the story as didactic narrative comprising nothing more than the hackneyed props

of fusty bourgeoise life. Conventional narrative techniques are jettisoned for a continual flow of images in which the animate

turns into the inanimate, the feminine into the masculine, the abstract into the concrete, reality into dream, and the object

into optical illusion. Man Ray employs a panoply of devices, film and narrative both, to achieve such masterly suggestion

and continuity: dissolves, double exposures, diagonally skewing the axis of the shot, rotating the image ninety degrees, optical

effects produced by light diffused through the prism of glass, animation, extravagant theater makeup, etc. In addition to

the fascinating artifacts in the film, such as Man Ray’s own mathematical objects and Pablo Picasso sculptures, there are

as well rather interesting protagonists. Roughly around halfway through, the surrealist poet Jacques Rigaut (1898–1929)

appears dressed as a woman, and one of the female characters, who is driving a car, is Alice Prin, known as Kiki de Montparnasse

(1901–53), one of the leading figures of bohemian Paris and Man Ray’s muse and lover for much of the 1920s.

Poetry – in this instance a specific poem penned by surrealist Robert Desnos (1900–45) – also forms the basis of the

other Man Ray film, L’etoile de mer (The Starfish). As the introductory caption states, this was a visual transposition

of “a poem by Robert Desnos as seen by Man Ray.” The female protagonist is again played by Kiki while there are two male

roles: one by Desnos’s friend André de la Rivière, also associated with the Paris surrealists, and the other by Desnos

himself. In 1929, Man Ray described how the film came about in the illustrated weekly Vu:

“One night I told my friend Robert Desnos, before he left on a two-month journey, that I would be happy to make a film

out of a script by him. I committed myself to finishing the film by the time he would be back, and the following morning,

as promised, Desnos brought me a script-like poem filled with very photogenic images, yet very simple, as such a poem inspired

by a starfish kept in a jar by his bed and written over the previous night, made half of dreams and half of reality.” More

than mere fascination with the inert beauty of a preserved echinoderm in a jar, prevalent in the poem is the motif of unrequited

love, which Desnos has mined from his unreciprocated feelings for the Belgian cabaret artiste Yvonne George (1896–1930).

The femme fatale of the text – inaccessible, forever elusive and protean – is transformed in the film into a starfish,

an object that one can take hold of and exert complete power over while at the same time it induces fear and remains untouchable.

Through allusions to women’s teeth and the goddess Cybele (the French original Si belle! Cybèle? forms a playful homophone)

the starfish, compared to “a flower of flesh,” becomes an elaborate erotic symbol for the vulva and castration anxiety.

The close association to the archetype of the female as eternal yet inaccessible guide is ultimately underpinned by the common

name of this marine animal: the French for “starfish” – l’étoile de mer – literally means “star of the sea,”

which brings to mind the Latin title Stella Maris connected to the cult of the Virgin Mary.

Man Ray (1890-1976), born Emmanuel Radnitzky, the multifaceted artist Man Ray – photographer, filmmaker, and inveterate

experimenter who actively took part both in Dada and in Surrealism – spent most of his life in Paris. It is only with slight

hyperbole that he has been called the “first Jewish avant-garde artist.” Born in Philadelphia, he was the oldest of three

children of Russian Jewish immigrant, but he grew up in Brooklyn, where his family, having changed its surname to Ray, moved

to participate like so many others in the garment industry. Even though Man Ray did not involve himself in the family business,

the industrial production of clothing still had a significant influence on his work. With his family’s support, he first

studied architecture, only to soon gravitate toward painting and visual art in general. One of the seminal moments of his

life was his stay at the artists’ colony in Ridgefield, New Jersey, where he found his first haven as an artist and met

both his first wife, the Belgian poet Donna Lecoeur, who wrote under the pseudonym Adon Lacroix, and in 1915 Marcel Duchamp.

It was Duchamp who waited for Man Ray to arrive at Gare St. Lazare when he moved to Paris in 1921. And Duchamp was also responsible

for introducing him to André Breton, Paul Eluard, Philippe Soupault, and many other artists. Once in Paris Man Ray hit the

ground running and involved himself in the artistic circle of Montparnasse – his output included photographs, films, and

other creative forms. Appearing in his shots, whether motion or static, were a pleiad of his present muses, the foremost of

whom were the dancer, actress, painter, and model Alice Prin, who went by the name Kiki de Montparnasse, the American photographer

Lee Miller, and the Swiss Surrealist Méret Oppenheim. He lived in Hollywood from 1940 to 1951, and he met his future wife

here, the dancer Juliet Browner, who had studied under Martha Graham (Man Ray and Browner were married in 1946 in a double

wedding with the Surrealists Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning). In 1951, he returned with his wife to live in Montparnasse,

which he had always considered his true home, and he lived here until his death in 1976. Man Ray is buried in the Cimetière

du Montparnasse, his headstone a kind of simple, rough-hewn stele bearing the epitaph “unconcerned but not indifferent.”

Notes to composers

Eliška Cílková (b. 1987) studied composition in Prague at the Jaroslav Ježek Conservatorium and the Academy of Performing

Arts under Hanuš Bartoň, graduating in 2014. She then studied for a year as a Fulbright Scholar with George Lewis and Georg

Friedrich Haas at Columbia University in New York, and under Fred Lerdahl’s guidance she experimented with her own compositions.

Earlier she had spent a year in Vienna at the Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst, and since May 2015 she has been

pursuing a doctorate at University of Birmingham. Her work has been focused on creating soundscapes, such as the projects

Sounds of the Chernobyl Zone and Pripyat Piano.

www.eliskacilkova.com

I began composing the score for Manhatta during my “Manhattan” year on a scholarship. My former professor there, the

eminent American composer George Lewis, helped me to refine my original concept. The music works as a single large composition

that freely illustrates the situations portrayed in the film while also presenting personal reflections on contemporary New

York. It creates a space between illustrating the film and borrowing some elements from American music of the 1930s for my

own approach to composition to come through.

After graduating from the Prague Conservatorium Šimon Voseček (b. 1978) studied in Vienna at the University of Music and

Performing Arts under Chaya Czernowin and Erich Urbanner et al. For the opera Biedermann und die Brandstifer (Biedermann and

the Arsonists) he was awarded the Outstanding Artist Prize in 2008. It premiered at Neue Oper Wien, and November 2015 will

see its British premiere in London at Independent Opera at Sadler’s Wells. Austria Radio (ORF) will be bringing out a CD

of the performance at the end of the year. With the support of an Austrian State grant he is currently composing another opera

for Sirene Operntheater. Voseček is a member of the Platypus New Music Group and the Schallundrauch performing arts agency,

in which as a performer and composer he creates productions for schools and youth groups. His music has been performed in

many countries in Europe, the Americas, and in Australia as well as at prestigious festivals such as Wien Modern, Klangspuren,

and MATA New York.

www.vosecek.eu

Šimon Voseček: Hallucinations / music to the film Mechanical Principles

À l’heure où les gardiens, à force de silence et fatigués de fixer l’obscurité, sont parfois victimes d’hallucinations.

At a time when the guardians, from silence and fatigue from staring into the darkness, are sometimes prey to hallucinations.

(from the play Roberto Zucco by Bernard-Marie Koltès)

After finishing a music gymnasium, Jan Ryant Dřízal (b. 1986) graduated in composition from the Prague Conservatorium under

Otomar Kvěch while also studying in the Department of Film Studies and Audiovisual Culture at Masaryk University in Brno.

At present he is continuing his studies of composition in the Masters program of the Music and Dance Faculty of the Academy

of Performing Arts in Prague under Hanuš Bartoň and at the Royal College of Music in London. Having been on scholarship

at the Estonian Academy of Music in Tallinn, he has also attended many courses on composition both at home and abroad. He

has achieved his greatest success with the chamber composition On a Dragonfly’s Wings for Prague Spring in 2013, the symphonic

ballet Alice in Wonderland, performed by the Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra, and first prize in the Czech Philharmonic competition

for the composition The Melancholic Chicken.

www.jan-ryant-drizal.eu

H2O fascinated me from the outset with its structure of images and cuts. Reflecting surfaces of water and the variations

created by an undulating element gave me the initial inspiration to work with rhythm and layerings. As the inner tempo of

Steiner’s shots and their length fluidly alter, the tempo of my music becomes ever more tranquil only to conclude by gushing

up again from the depths. The harmony is a simple interplay between two major keys – A and C – to represent the two elements

of the water molecule – hydrogen and oxygen.

Polish composer Jacek Sotomski (b. 1987) graduated from the Karol Lipiński Music Academy in Wrocław, studying composition

under Agata Zubel and Cezary Duchnowski. In addition to compositions for solo instruments, chamber ensembles, small and large

orchestras, he has also created electronic music, both in the form of fixed audio files (“tape music”) and live electronics,

often with the accompaniment of acoustic instruments, and composed music for plays. His work has been performed at many festivals,

such as ISCM World Music Days, Young Composers Meeting, Warsaw Autumn, Musica Polonica Nova, Musica Electronica Nova, Ostrava

Music Days, and Cinemascope. He has participated in workshops and masterclasses with the ensemble musikFabrik and the composers

Bernhard Lang, Jennifer Walshe, Peter Ablinger, and Louis Andriessen among others. In 2011, he and Mikołaj Laskowski formed

a band that uses old cassette players as instruments. To date they have released 3 LPs.

www.sotomski.eu

Emak Bakia I found it somewhat odd to score a silent movie nearly 100 years after it was made, but odd in a good way. My

image of its reception in the 1920s along with its title gave me a single feeling – maladjustment. I wanted my music to

be from a different world than the movie’s, to sound like it does not exactly fit the whole situation. I don’t really

see it as a soundtrack or as musical accompaniment to the film. It is an entirely independent entity that every so often intersects

with the visual layer.

Martin Klusák (b. 1987) first became interested in composition by creating soundtracks and music for film as a student at

the Film and TV School (FAMU) in Prague and later as a sound designer. Since 2010, when he began to study composition at the

Music and Dance Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (HAMU) under Ivana Loudová, he has focused on concert

work. Over the past few years his work has garnered a number of awards: first prize in the competitions held by the Prague

Philharmonic Choir (2012) and the Janáček May International Festival (2014); the Public’s Choice Prize given by BERG Orchestra

(2013); and the prize for the best Czech electroacoustic composition in Musica Nova (2011, 2014). He composed the score for

the film Cesta do Říma (Journey to Rome), which had its premiere at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in 2015.

He also contributed music and sound elements to the film Velká noc (The Great Night), which was awarded a first prize at

the Jihlava International Documentary Film Festival in 2013.

www.martinklusak.cz

’Étoile de mer Rather than preserve the original work (by composing background music to the fluid flow of the film), my

intention was to create a dialogue between sound and image to enhance the silent film with my own perspective and thereby

give it a new meaning that Man Ray could not have contemplated. I was influenced by the fact that Robert Desnos, who wrote

the poem “L’Étoile de mer,” died in 1945 in Terezín. I have “cut out” characteristic music-sound passages to accompany

the images in a disparate context with the objective to imprint information on the fate of the poet and his work.

2014 - The City Without Jews: Hugo Bettauer and the Republic of Utopia

Austria 1924

Directed by: Hans Karl Breslauer

Conservation, reconstruction and digitization: Filmarchiv Austria

Music by: Petr Wajsar (2014), world premiere

Performed by: BERG Orchestra conducted by Peter Vrábel

FILM

The film The City Without Jews (Die Stadt ohne Juden), made by Austrian director and producer Hans Karl Breslauer (1888–1965),

was based on the novel of the same name by author, journalist, and bon vivant Maximilian Hugo Bettauer (1872–1925). For

decades it was assumed to be lost, until an incomplete copy was discovered at the Nederlands Filmmuseum in 1991.

The film premiered in 1924 in two phases, and in neither case did it have much luck. Its first release to movie theaters

in July met with technical difficulties, which ended with a falling out between Breslauer and Bettauer, who immediately thereafter

distanced himself from the film. A second premiere took place on October 11, 1924, in a movie theater in the Vienna suburb

of Neustadt. This showing was met by a violent protest from the local Hakenkreuzler who attacked attendees and disrupted the

event by throwing stink bombs into the theater. The premiere in Berlin in 1926 provoked protests as well, and the film was

also excoriated in the liberal press as tendentious and promoting negative stereotypes. The Berlin fiasco and the prior public

protests and scandals eventually led to the film being banned in the United States and the cancellation of its New York premiere

planned for 1928.

The City Without Jews got a second life in Amsterdam in 1933 shortly after the advent of sound film. What fortuitous circumstances

revived interest in a silent movie? It was not a marketing ploy but the radical transformation of the political situation

in Germany that provided the impetus. The Theater Carré, which staged operettas a cabarets, decided in mid-July 1933 to respond

to events in Germany by holding a series of public screenings of the film that included an opening recital by the chief cantor

of Warsaw Gershon Sirota. The program was explicitly conceived to rouse the Dutch public from their indifference toward the

growing threat of the anti-Semitism that had officially become a part of German politics and state propaganda. The critics

naturally did not give the initiative a positive reception. They accused the organizers of doing a disservice by showing a

badly acted, old German silent film larded with folkloric motifs and intertitles hastily translated into poor Dutch. The critics

complained that the film’s reputed low production values, its scenes coming off as comical rather than tragic, made light

of the gravity of the situation German Jews found themselves in, and as such it was counterproductive. The only bright spot,

they said, was that by a fluke the author of the novel on which the film was based, Hugo Bettauer, had the foresight years

ago to predict what was actually coming to pass . . .

Whether this was indeed a fluke is debatable, but it’s clear that Bettauer considered this first of his four “grand Vienna

novels” that he wrote and published between 1922 and 1924 a satire. As he explained in Die Börse, one of the many periodicals

he regularly contributed to, his immediate motivation to write the novel was graffiti on the walls of one of Vienna’s public

toilets that said, “Hinaus mit den Juden!” (Jews out!). This anonymous eruption of zeal was the trigger that activated

Bettauer’s imagination. As he put it: “The image of this jovial young man, the kind we often see on posters adorned with

a jaunty swastika, the kind we often hear on the tram commenting aloud on what the Wiener Stimmen has to say about the Christian-German

purification program, put the idea in my head of what would happen to Vienna if all the Jews actually took the calls for them

to leave seriously.”

And what would happen? The film satirically answers this, and save a couple of unnecessary modifications its plot is largely

faithful to the novel, which teases out all the implications of such an exodus down to the last detail.

A narcissistic, rather inept politician, the populist chancellor of the fictional Republic of Utopia, is under pressure by

mass street protests and the anti-Jewish mood of conservative parliamentarians, who fashion themselves as defenders of Christian

morality and traditional values while vehemently promoting the idea of Greater Germany disseminated mostly in louche pubs.

In a confidential conversation with the head of the Church, the chancellor mentions that the situation has become intolerable

and one way to quickly resolve it would be for the government to heed the vox populi calling for the expulsion of Jews. When

he enacts this plan, however, it gradually becomes clear that those who lent the capital city of Utopia, which is easily recognizable

as 20th-century Vienna, its unmistakable cosmopolitan élan and bolstered its position as a political, commercial, and cultural

center, were the Jews. And these were not only the wealthiest Jews, but Jews of all social strata. Without them, the city

loses more than its allure and diversity, it also suffers economic and intellectual decline and ends up politically isolated.

With provincial philistinism now rampant and the theaters putting on the tacky farces written by parochial moralists for a

cast of earthy soubrettes and country boys, with the show windows of boutiques that once displayed the latest in Parisian

fashion now filled with long johns and shapeless bodices of fustian and loden, and the elegant cafés now dives serving cheap

booze and beer, the news reaching the chancellery paints an ever more dire picture. Business and trade were dwindling, inflation

was on the rise, and the currency was mired in a downward spiral. The plot thickens and culminates in the madhouse scenes

in which the obstinate anti-Semite and parliamentarian from the Greater German Party begins to deliriously rave that he is

a Zionist. Though it has been lost, the film, like the book, has a happy ending (the final sequence has been reconstructed

with stills and text). Unfortunately Bettauer’s otherwise chillingly prescient vision in reality did not have a happy end.

The digitized version of the film was reconstructed from an incomplete release print that was found in the Film Museum in

Amsterdam. It totaled six reels of celluloid measuring 1635m in length. When compared with the archival records that list

the Vienna release print at 2400m, then clearly about 750m of film have been lost. The film was composed in “virage,”

a process of color tinting, soaking the film in dye and staining with emulsion, or toning, which replaced the silver particles

in the emulsion with color pigments. Particular sequences of the film have their own particular tint, and this color coding

becomes an integral component of the narrative. The German intertitles are new, and in some cases they are taken directly

from the novel. The Czech and English intertitles were translated specifically for the screening in Prague. The restored version

of the film was reconstructed and digitized by the Filmarchiv Austria, which concurrently published a comprehensive study

as part of their series Film und Text: Guntram Geser, and Armin Loacker, eds. Die Stadt ohne Juden. Vienna: Filmarchiv Austria,

2000.

Maximilian Hugo Bettauer (1872–1925): Life as an adventure novel

Hugo Bettauer was born on August 8, 1872, in Baden bei Wien the youngest of three children of the Jewish stockbroker Arnold

Bettauer and his wife Anna, née Wecker. Bettauer’s father died when he was only a year old, and his mother moved with the

children to Vienna, where from 1886 he attended the Kaiser-Franz-Joseph Gymnasium. Upon reaching the age of eighteen in 1890,

he converted to Protestantism and volunteered for a year of service with the Imperial Tyrolean Rifle Regiments. Evidently

subjected to bullying, he deserted after five months. After this episode, the entire family relocated to Zürich. It was here

that Bettauer became interested in journalism, and in short order he began his studies in this field. In 1896, he married

the love of his life from Vienna, Olga Steiner, and after Bettauer’s mother died the two traveled to the United States.

This first trip to America marked the beginning of his quick rise in the ranks of journalists and writers, yet not without

its share of scandals and dramatic twists and turns.

At the beginning of 1899, Hugo and Olga Bettauer returned to Europe and settled in Berlin, where he tried to make a name

for himself as a journalist. His son, Gustav Heinrich, was born in the middle of that year, but his marriage was falling apart,

caused to some extent by the fact that he had lost nearly all his wealth on bad investments. During his time as a journalist

for the Berliner Morgenpost he was involved in a scandal that ultimately led to his being sued in 1901 for defamation, and

when found guilty, he was banished from Prussia.

After leaving Berlin, Bettauer first went to Munich, where he worked for the cabaret Die elf Scharfrichter, and then to Hamburg,

where he wrote for a food magazine. He met his second wife, Helene Müller, at this time, and after the wedding they went

overseas, settling in New York where he worked as a reporter for two German newspapers, Deutsche Zeitung and the New Yorker

Staatszeitung. He became a father for the second time in 1904 when another son, Reginald Parker, was born. In February 1907

Bettauer began to contribute to the New Yorker Morgen-Journal, which targeted German-speaking immigrants and serialized several

of his popular novels: Im Kampf ums Glück (The Struggle for Happiness); Im Schatten des Todes (In the Shadow of Death); Aus

den Tiefen der Welstadt (From the Depths of the Metropolis).

Bettauer returned to Vienna in 1910 as a correspondent for the New Yorker Morgen-Journal while also writing for the newspaper

Die Zeit. He tried to enlist in the army in 1914 but was rejected on grounds that he was an American citizen. He spent the

years 1914–1918 as editor of the liberal daily Neue Freie Presse, and after the war he continued his work as a correspondent

for New York American and New Yorker Staatszeitung, also working with the American Relief Committee for Sufferers in Austria.

The apex of Bettauer’s career as both a journalist and novelist was in 1920. Even though his literary output no doubt belongs

in the entertainment genre, not all of his work can be called pulp, as it was labeled by the literary and a few of the film

critics of the day. During this period Bettauer was pumping out three to five novels a year, which were first released in

magazine installments and then later in book form, with many being adapted for film (for example, Faustrecht (Law of the Jungle)

and Hemmungslos (Unscrupulous), both from 1920).

Between 1922 and 1924 Bettauer published in succession four of his “grand Vienna novels.” The City Without Jews came

out first and was followed by Der Kampf um Wien (Fight for Vienna, 1922), Die freudlose Gasse (The Joyless Street, 1923),

and Das entfesselte Wien (Vienna Unleashed, 1924). In February 1924, he and Rudolf Olden (1885–1940), a fellow journalist,

writer, human rights activist, and pacifist, began to publish their own magazine Er und Sie. Wochenschrift für Lebenskultur

und Erotik (He and She: A Magazine for Lifestyle and Eroticism), which uniquely for that time addressed generally ignored

taboo topics such as prostitution, homosexuality, abortion, as well as unemployment, homelessness, and other acute social

problems faced by the young Austrian state exhausted by the First World War.

As soon as this magazine began to appear, Bettauer became the target of rank anti-Semitic attacks. A representative of the

Christian Socialists, Anton Orel, wrote this about him in March 1924: “The Jew Bettauer has begun to publish his filthy

Jewish magazine, which much like a profiteer exploits the squalor of others, and only deepens it and in typically Jewish fashion

makes money off it.” Indeed, similar attacks on Bettauer were not isolated. Another such text appeared in April 1925 on

the pages of the anti-Semitic fortnightly Der Weltkampf, published by one of the later chief ideologues of the Third Reich,

Alfred Rosenberg. The squib was titled “Der Fall Bettauer: Ein Musterbeispiel jüdischer Zersetzungstätigkeit” (The Case

of Bettauer: A Perfect Example of Subversive Jewish Activity). Rosenberg wrote that Bettauer was a “typical example of Jewish

degeneracy and perversion.”

Unfortunately the increasing assaults both verbal and in print did not stop there. On March 10, 1925, Bettauer was attacked

at the magazine’s office by Otto Rothstock, a dental technician and fanatical supporter of the NSDAP. He shot Bettauer several

times, and after two weeks of fighting for his life in a Vienna hospital, Bettauer died of his wounds. Though there was plenty

of speculation as to the motives, they were never entirely made clear. Rothstock stated that he was incensed by Bettauer’s

evident moral laxness and, as he literally put it, impertinence. Rothstock was convicted, but the court determined that he

had been insane at the time he committed the murder. He was therefore sent to a psychiatric hospital and at the end of May

1927 was given his unconditional release without further explanation.

MUSIC

The new score for the City Without Jews was specifically commissioned by BERG Orchestra from composer Petr wajsar, with whom

it has collaborated since 2000. The first meetings between them

were less about music composition than other forms of creative projects: for BERG’s performance of Olivier Messiaen’s

Three Small Liturgies wajsar created a remarkable acoustically faithful electronic

emulation of the ondes Martenot, an instrument that was unattainable in the Czech Republic. Wajsar’s acoustic imagination

was crucial in undertaking such a difficult assignment. A series of

regular meetings between BERG and wajsar followed to discuss his work as a composer. you can find the fruits of this collaboration

on the BERG Orchestra website, but to mention two, there was

the drum’n’base inspired Drum’n’BERG (2007), which won the Public’s Choice Prize, and 8 Sentences on Fans (2013),

which won both the Public’s Choice Prize and the NUBERG Grand Prize. All the

competition results can be found in the NUBERG section on the BERG website. Petr Wajsar on the score for The City without

Jews:

“Like many of my colleagues, I’ve been asked by a number of Prague’s film clubs to accompany a silent-film screening

on the piano. So when BERG Orchestra commissioned a score for this film, it

did not take long for the entire concept for the evening to come to me (actually, it did, but it sounds much better in a

program to say it didn’t). The idea came to me at a music festival where there was

a sound installation with an old upright piano that you could play. I spent many long intimate moments with the piano nostalgically

recalling bygone eras, and caught in its spell, I decided it should

have a solo part in the score. The composition literally calls for an out-of-tune piano so that the authenticity of the

sound would have the greatest effect.”

THE COMPOSER

Petr Wajsar (b. 1978) is a composer as well as a bass-guitar player and a vocalist. He studied composition at the Prague

Conservatory under Milan Svoboda (popular music) and the Jaroslav Ježek Conservatory

under Stanislav Jelínek (jazz), and classical composition under Prof. Václav Riedlbauch at the Academy of Performing Arts

in Prague (AMU). He has composed concert music for BERG

Orchestra, Epoque Quartet, Agon Orchestra, the Hradec Králové Philharmonic, and others. In addition, International A Cappella

Competition Vokal Total 2014 in Graz, Austria. He has written music for

the ballet Maryša, the musical Pornstars, for recent productions of Hamlet (Švandovo Theater 2013) and The Life of the

Insects (National Theater, 2014), and for feature and documentary films.

wajsar won the Public’s Choice Prize in the 2008 NUBERG competition and the NUBERG Grand Prize in 2013.

www.wajsar.cz

THE PERFORMERS

Peter Vrábel is a Slovak conductor who lives and works in the Czech Republic. while still a student at the Academy of Performing

Arts in Prague he founded the BERG Orchestra in 1995 and conceived

its musical direction. Under his direction, BERG today is highly regarded for its incomparable performances of music both

contemporary and from the 20th century. Vrábel collaborates with

the top Czech composers, providing inspiration to the younger generation of emerging composers and performers by creating

opportunities for their music to be heard. He has conducted contemporary

Czech music both at home and abroad. A recipient of the Gideon Klein Prize, his work with BERG Orchestra was commended in

2010 for artistic excellence and the promotion of Czech music

by the Czech section of the International Music Council of UNESCO. BERG Orchestra is one of the leading music ensembles,

having for years brought a breath of fresh

air to the Czech music scene. Its innovative concerts have attracted the public’s attention with its combination of contemporary

music, dance, film, theater, and video projections. BERG often performs

outside the traditional concert hall setting, and it is the only Czech orchestra that regularly commissions and performs

world premieres of Czech composers, particularly those of the younger

generation. It has to date performed nearly a hundred world premieres. BERG also performs Czech premieres of world-class

foreign composers, such as the staging of Schwarz auf Weiss (Black on

white) by Heiner Goebbels, music to the video projection Up-Close by Michel van der Aa, the unique concert-length composition

In vain by Georg Friedrich Haas, and György Ligeti’s legendary work

Poème Symphonique for 100 metronomes. BERG has performed a number of its own original projects as well, such as its collaboration

with the dance troupe 420PEOPLE, the director Petra

Tejnorová, the choreographer Mirka Eliášová, and the directorial tandem SKUTR. The orchestra has worked with leading

Czech institutions, among them the National Theater, the Jewish Museum

in Prague, the DOX Centre for Contemporary Art, the Strings of Autumn festival, the Prague Spring International Music Festival,

the Music Forum, and others, and has taken part in many educational

projects.

www.berg.cz

BERG Orchestra and guests*

Alexej Aslamas, Roman Hranička, Marek Ferenc – violin

Ilia Chernoklinov – viola

Lukáš Polák – violoncello

Antonín Šturma* – double bass and bass guitar

Zuzana Bandúrová – flute

Irvin Venyš – clarinet, bassclarinet

Tomáš Bürger – French horn

Tomáš Bialko – trombone

Oleg Sokolov – percussions

Petr wajsar* – piano and other sound effects

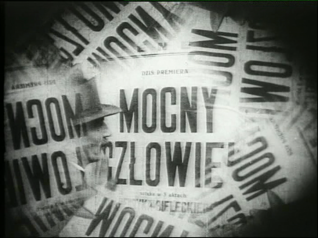

2013 - Bottomless Soul: Henryk Szaro and Polish Expressionism

The Strong Man

Poland, 1929, 78 min.

Directed by: Henryk Szaro

Conservation and digitization by: Filmoteka narodowa Warszawa, PL

Music by: Pink Freud

The Strong Man (Mocny człowiek) was shot in 1929 by Henryk Szaro, a leading director of film and stage as well as screenwriter

in Poland. The film is based on the eponymous novel from Stanisław Przybyszewski’s (1868–1927) voluminous trilogy. The

main character is a talentless hack named Henryk Bielecki (played by Grzegorz Chmara) who yearns for literary stardom and

material wealth. His desire for money and fame is so overpowering that he is willing to do anything, even commit murder. And

this he does to his friend, the gifted writer Jerzy Górski (played by Artur Socha), by convincing him that his new work

is nothing more than mediocre and then leading him to a morphine addiction. Overcome with doubts about the quality of his

work, Górski believes Bielecki, and his drug dependence eventually destroys him. Bielecki then takes the manuscript and

publishes it under his own name, and this brings him the recognition and riches he craved. Yet his solace in worldly pleasures

does not last for long. Bielecki’s growing inner turmoil decides his fate to bring his phony career to a bitter end, climaxing

in a deranged final scene. With its innovate camerawork, The Strong Man is a brilliant example of the psychological drama

from the silent era. The suggestive though not affected acting shifts the aesthetic from the classic Expressionist films

toward something closer to the celebrated films noir of the 1940s. Szaro was able to translate into the language of film

the panoply of dark images from Przybyszewski’s writings, which he based on his extensive knowledge of psychiatry and the

occult sciences. Thought lost for decades since the end of the Second World War, the film was rediscovered in the Royal

Film Archive in Brussels in 1997, and it is one of the few surviving Polish silent films. CINEGOGUE will be showing a restored

version from the National Film Archives in Warsaw.

Henryk Szaro (born Henoch Szapiro, 1900–1942)

Szaro was one of the pioneers of interwar Polish cinema. After studying in Petrograd and Moscow – he said to have studied

under Vsevolod Meyerhold and was an assistant to theater and film director Alexander Granovsky in the Moscow State Jewish

Theater (GOSET) – he returned in 1924 to his native Warsaw after a short stint in Berlin with a cabaret troupe of Russian

émigrés called Blue Bird. That very year he had his directorial debut in the newly opened Jewish theater Skala with a production of

Yoshke Muzikant, Ossip Dymow’s popular farce from the world of the East European shtetl. Szaro’s career as a film director

began the following year with Rywale (The Rivals) and Lamedvovnik (One of the 36 – the screenplay was by established Jewish screenwriter

and photojournalist Henryk Bojm). He followed up this double debut with the cabaret thriller Czerwony blazen (The Red Clown,

1926) and then Zew morza (The Call of the Sea, 1927), Dzikuszka (1928, a melodrama based on the novel by Irena Zarzycka),

and Przedwiośnie (The Coming Spring, 1928, based on the novel by Stefan Żeromski with a screenplay co-written by Polish

Jewish poet and Futurist Anatol Stern).

Szaro’s first silent films were produced by the prominent Warsaw Jewish photographer Leo Forbert (?–1938) and shot by

the legendary cinematographer and innovator Seweryn Steinwurzel (1898–1983). Forbert has been unjustly forgotten in the

history of interwar Polish cinema given the large role he played in getting the Polish film industry back on its feet after

the First World War. In the 1930s, Szaro directed another nine films, though this time they were all talkies. The last of

them, Klamstwo Krystyny (Krystyna’s Lie), was released in 1939. It is not clear what became of Szaro at the beginning

of the Nazi occupation. Some claimed that he managed to flee to Vilnius, Lithuania, and then returned to Warsaw where he

was interned in the Jewish Ghetto. His death, however, is unfortunately beyond doubt as it appears in the diary of Adam

Czerniaków, head of the ghetto’s Jewish Council, who wrote: “June 9, 1942 – Morning at the municipal office. Last

night at least a dozen people were executed for smuggling etc., including the director Szaro and his father-in-law Goldman.”

2012 East & West: Picon – Kalich – Goldin and the Old-New World

East and West a.k.a. Mazl tov

Austria, 1923, 85 min.

Directed by: M. Goldin, Ivan Abramson

Conservation and digitization by: The National Center for Jewish Film, USA

Music by: Jan Dušek (2012), world premiere

Performed by: BERG Orchestra conducted by Peter Vrábel

2011 - The Eccentricity Factory: Kozintsev – Trauberg – Yutkevich and FEKS

The New Babylon

USSR, 1929, 93 min.

Directed by: Leonid Trauberg, Grigorij Kzincev

Conservation, reconstruction and digitization by: Absolut Medien, Germany

Music by: Dmitrij Šostakovič (1929)

Performed by: BERG Orchestra conducted by Peter Vrábel

Short film

A Child of the Ghetto

USA, 1910, 15 min.

Directed by: D. W. Griffith

Conservation and digitization by: The National Center for Jewish Film, USA

Music by: Jan Dušek (2011), world premiere

Performed by: BERG Orchestra conducted by Peter Vrábel

2010 - The Pursuit of Happiness: Salomon Michoels and the Moscow State Yiddish Theater GOSET

Jewish Luck a.k.a. Menachem Mendl

USSR, 1925, 100 min.

Directed by: Alexander Granovsky

Conservation and digitization by: The National Center for Jewish Film, USA

New music composed and performed by: Miloš Orson Štědroň (2010), world premiere

2009 - Hungry Hearts: From Shtetl to Hollywood

Hungry Hearts

USA, 1922, 80 min.

Directed by: E. Mason Hoper

Conservation and digitization by: The National Center for Jewish Film, USA; British Film Institute, UK; Samuel Goldwyn Company,

USA

Music by: Jan Dušek (2009), world premiere

Performed by: BERG Orchestra conducted by Peter Vrábel

![[subpage-banner/3_Programavzdelavani_2.jpg]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/subpage-banner/3_Programavzdelavani_2.jpg)

![[design/2013/Twitter.png]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/design/2013/Twitter.png)

![[design/2013/Instagram.png]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/design/2013/Instagram.png)

![[homepage-banner/incident.jpeg]](https://c.jewishmuseum.cz/images/homepage-banner/incident.jpeg)